Listen to yourself. Our inner voices can be annoying, but they represent something we feel deep down. People who have done impressive work in social action often talk about what sounds like a nagging sensation they found hard to quiet. There are many ways to contribute, but you’ll be most effective in something that sparks an urge in you.

An upstander is the opposite of a bystander. A bystander is someone who stands by while others are being bullied, maligned, or mistreated. An upstander is someone who stands up to protect and advocate for the victim. We are sadly seeing a surge of hate, both online and in the real world. Many vulnerable minorities feel threatened and under attack. What measures are individuals, communities, and organizations taking to stand up against Antisemitism, Racism, Bigotry, and Hate? In this interview series, we are talking to activists, community leaders, and individuals who are Upstanders against hate, to share what they are doing and to inspire others to do the same. As part of this series, we had the pleasure of interviewing Author Donald Blair.

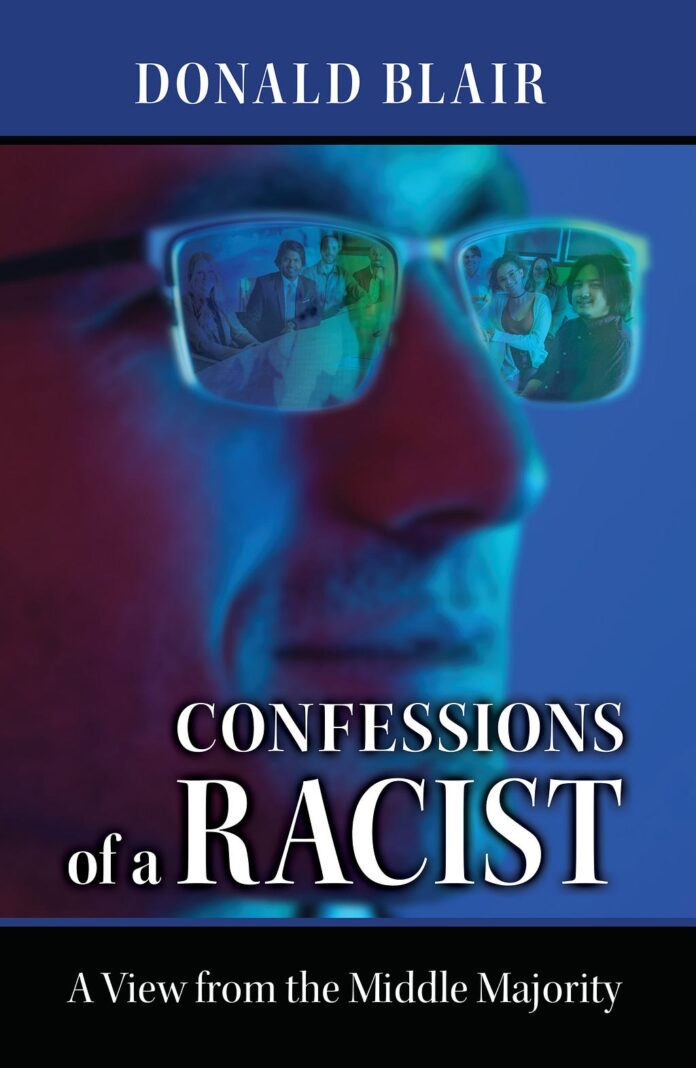

Donald Blair is the author of Confessions of a Racist: A View from the Middle Majority. He did not come to the subject as an established academic or professional with formal credentials in sociology, political science, or law. But that’s proved to be his main qualification as he shares the perspective of an ordinary person struggling with how we can better live up to the American ideal. As experts and pundits grow increasingly divided, Blair gives voice to those more concerned with doing the right thing than with contrived displays of controversy and confrontation. Blair comes to the topic of racial equity as a mindful member of the Middle Majority, a group accustomed to keeping to themselves as they try to avoid the heightened emotions and discomfort that characterizes discussions of race in America. In Confessions of a Racist, Blair has garnered significant attention by presenting the unique Middle Majority perspective that defies the conventional wisdom of both the conservative and liberal establishment.

Thank you so much for doing this with us! Before we dive in, our readers would love to get to know you a bit better. Can you tell us your “Origin Story”? Can you tell us the story of how you grew up?

I grew up on the right side of the tracks. I was raised in an almost entirely White, upper middle-class suburban neighborhood. Our parents sent us to a parochial Catholic grade school that taught a classic 1970s set of enlightened views of acceptance and inclusion. The only problem was that it was an almost entirely theoretical exercise. We were taught the evils of prejudice, said the right things, and had fundraisers for the underprivileged. But we had very little interaction with anyone outside our community. So our professed values were never put to the test in a meaningful way.

Can you share a personal story of how you experienced or encountered antisemitism, racism, bigotry, or hate? How did that experience shape your perception and actions moving forward?

As I grew older and expanded my world, I naturally became more personally and professionally connected with people of different backgrounds. I think I wised up a little bit in regards to understanding more of the real and everyday obstacles that people faced who didn’t fit the model of the majority middle-class “average” American. But I still had the view that the country was steadily progressing towards a place of racial equity. The election of Barack Obama in 2008 seemed to be a resounding confirmation of that progress. That all changed afterwards of course, when the post-Obama backlash revealed a country far more divided over core issues and values than I suspected. I always knew there were people with racist views, but I thought they were confined to a declining fringe. Suddenly some people that I knew well, “regular” people who I thought shared the same basic moral code, felt free to express views that ranged from uncharitable to inexcusable.

Can you describe how you or your organization is helping to stand up against hate? What inspired you to take up this cause?

In truth, I’m not certain that I am standing up against hate. I’m just trying to stand up for what’s right from a social, political and economic point of view. The strength of this country on every level is based on allowing individuals the freedom to pursue their full potential. It serves us all to have a say in how best to achieve that going forward. Yet as the voices on the far sides of the political divide have grown louder and angrier, the voice of what I like to call the Middle Majority has gotten quieter and more cautious. As a result, the arguments between the extremes dominate the bulk of our civil discourse. This is not only unrepresentative of our country, it is ineffective. The vitriol carries little practical guidance as to the policies and programs we should stop, start or continue. This led me to write Confessions of a Racist in order to bring the Middle Majority back into the conversation. Most of those I shared the book with tried to dissuade me from doing it. In their eyes, there was little to be gained, and I was only setting myself up to be attacked from both sides. They may be right, but I found it increasingly hard to see the problem and not make some effort to address it. My voice is small and lacking in credentials for such a large and complex subject. The most I can hope is that it awakens people of similar feelings and greater skill to join the fray.

Can you tell us the most interesting story that happened to you since you began your work as an Upstander? Could you share an inspiring story that demonstrates the impact your efforts have had on an individual or community?

You can never be certain of the impact you’re having with a book. The reader is at a distance, so it’s hard to tell if you’ve gotten something across that positively affects their thinking. But the readers I have been able to interact with directly told me a similar story of how they went into the book expecting one thing and then coming away with something entirely different. They were anticipating more of a memoir or an emotional appeal. There was a bit of that, but it was more about weighing the arguments around what we can and should be doing. Most importantly, they reacted to the arguments by putting forth their own counter-arguments. That reinforced my hope that thoughtfulness would engender more thoughtfulness. A competition of ideas can be passionate, hard-fought, and even adversarial, but ultimately promotes a stronger understanding. That seems a far better place than the diatribes that just seek to demonize opposing viewpoints. So it was encouraging to think the book pushed some people into engaging in a more productive way.

In your opinion, why do you think there has been such a surge of antisemitism, racism, bigotry, & hate, recently?

Bigotry and hate is born of fear and insecurity. Society has not caught up to the changes that have been wrought upon it from multiple sides. For example, the widening disparity in wealth and decline in class mobility has made many people pessimistic of their economic futures. Wars between sovereign nations have been replaced with borderless groups who attack civilian citizens instead of their militaries. When you add other disruptions like gender redefinitions, social media culture, the advent of AI, and climate change into the mix, it throws people into a state of perpetual aggravation. The easiest emotional crutch to deal with this aggravation is to find an enemy to blame. Trying to understand the effects of things like inter-related government policies, economic forces, and the origins of social trends is hard. It’s much simpler to point at someone outside your world and point blame. When cultures go through these types of changes, they look to their peers, their leaders, and their heroes to set the tone. Too many of those figures have given our country the social permission to value confrontational posturing over meaningful discussion. That’s why I feel it’s time for ordinary people to take on more of the conversation.

Are there three things the community/society/politicians can do to help you address the root of the problem you are trying to solve?

I believe that the drive towards racial equity needs to take on a more systematic scale than a personal scale. By that, I mean many previous efforts were designed to open up institutions and opportunities to a wider range of citizens to redefine what was possible. For instance, opening up Ivy League colleges to hundreds of more minority students helped change perceptions of what was possible. But it will take a different type of effort to get millions of more underrepresented minorities through college. The three elements required to achieve that include:

- Try to separate root causes from symptoms — For example, the government tries to encourage more minority business owners by setting aside a certain number of contracts for minority-owned businesses. But what these businesses often lack is the same access to capital. Awarding contracts only indirectly addresses the capital problem.

- Look to results more than symbols — A lot of public attention is put on “the first”: the first one of a certain background to have this job, win that election, or receive this award. But what we really need are programs that affect meaningful numbers of people. Inspiration is great, but it doesn’t always scale.

- Be open to trying new things — I was strongly opposed to the idea of universal basic income when I first heard it. It seemed to violate all the tenets of free enterprise that has made the US the most successful economy in history. But I heard someone frame it as a simpler and more cost-effective way to implement our current range of separate and bureaucratic welfare systems. It made me rethink it, and ultimately see it is at least worth testing to see how it may work.

What are your “5 Things Everyone Can Do To Be An Upstander”?

I’m not qualified to coach others on how to be an Upstander, especially since what I’m doing pales in comparison to people who are dedicating every part of their lives to it. But I can share what I’ve observed in those who I admire:

- Start in small ways. Fans of Shakespeare (or Willy Wonka), may remember the line “How far that little candle throws his beams! So shines a good deed in a weary world.” Many of the most impressive change agents didn’t set out to change the world, just one small part of it.

- Listen to yourself. Our inner voices can be annoying, but they represent something we feel deep down. People who have done impressive work in social action often talk about what sounds like a nagging sensation they found hard to quiet. There are many ways to contribute, but you’ll be most effective in something that sparks an urge in you.

- Turn good thoughts into good deeds. You can see many well-intentioned social media posts from people drawn to right some wrong. But social media is the junk food of social action. It may fill you up, but there’s no real nourishment involved. But a true effort, a small deed to move things in the right direction is not too much to ask of anyone. Translate the voice in your head into a little bit of action.

- Be humble. None of the heroes I’ve met think of themselves as heroes. They accept help gladly, they credit others, and they see themselves in service to a larger objective. While they may be teaching, they never stop learning.

- Know your audience. Change involves persuasion. Different people are persuaded by different things. Some people are beyond persuasion. Don’t waste time on people you can’t move. For those you can move, try to understand issues from their perspective in order to compel them to your side.

How do you handle the emotional toll that comes with being an Upstander?

Anyone would have to expect a large dose of criticism and insults for writing something like Confessions of A Racist. I prepared for that by keeping that in mind when I was writing. I wanted to be as fair, honest, and thoughtful as I could be. That was mostly to create something someone else might find worth reading, but it was also to protect myself. If I’d done it with any other agenda in mind, it would have led to second-guessing my effort. I think we are especially susceptible to critics when we feel they’re piercing some persona we’re trying to project. While I hope my views are always open to change as I learn, I can say that everything I wrote was rooted in what I believed when I wrote it. That takes some of the sting out of the attacks, because I can see it as directed more at the ideas than at me.

If you were in charge of the major social media companies, what would you do to address the hate on the platforms? Could you share specific strategies or policies that you believe would be effective in addressing hate on social media platforms?

Sadly, far better minds than mine have tried to address this with little effect. But I think two things would help. One is there are some platforms that allow anonymity which I think encourages hateful behavior. If people aren’t willing to stand by their words, then I don’t think they have a right to them. The other is that I believe Congress needs to revise Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act. This law was made in the early days of the commercial internet, and allows Meta, X and other platforms to claim that they are only publishers of third-party content, for which they bear no responsibility. But they are monetizing that content, deciding where and when it shows up, and maximizing time spent on their platform without regard to its effects. I think that if you’re making money off content, you need to be responsible for it. Just as we hold manufacturers responsible for the pollution coming out of their plants, we need to hold the social media platforms responsible for the pollution of hate and misinformation they spew.

How would you answer someone who says: “Hate speech is permitted under the US Constitution. Why are you so worried about permitted, and legal speech?”

Hate speech is clearly protected by the First Amendment except to the extent it can be tied directly to inciting a hate crime. I find myself in reluctant agreement with that as a price for the freedom of speech that is core to our national essence. The idealistic hope is that we can educate ourselves enough to recognize hate speech for what it is, and dull its effects. In that light, what is even more concerning to me is misinformation. As the late Senator Daniel Moynihan said “everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts.” Related to the previous question, I believe that social platforms should pay a price for being indifferent to amplifying conspiracy theories and outright lies. Right now, they are profiting from them.

Are you optimistic that we can solve this problem in the United States? Can you please explain what you mean?

Yes, I am optimistic overall that the US can get better. Despite what seems like more than a few steps backward in the past decade, there is a larger trend at play. Martin Luther King Jr made famous the quote that “the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.” The last decade has certainly slowed us down, but I think the march towards a fairer society continues. The problem, of course, is that the more time it takes to close the racial equity gap, the more people continue to suffer from its effects.. That’s why I’m trying to engage people who aren’t part of the conversation. If nothing else, demographics will be a positive force in the long-term, but we need to accelerate the pace.

What advice would you give to someone who wants to become an Upstander but doesn’t know where to start?

Our behavior tends to be an accumulation of our habits. I’ve found that the best way to develop a new habit is to start small. I’d have a hard time making dramatic changes to my eating habits, but I can eat a little less processed food, and a little more fresh food without feeling deprived. Then, I start to like fresh things more, and things go on from there. There are small things we can do to try to be better citizens that don’t require becoming an activist. We can volunteer for an organization, donate to a program, or even encourage a friend to vote — any little thing that reinforces a contribution to the community. Pick something small and easy and see where the habit takes you.

In what ways can education be leveraged to combat antisemitism, racism, bigotry, and hate?

In this respect, education is similar to medicine. It’s essential to advance our health, but it’s also subject to abuse. In the broadest sense, we all stand to benefit from educational experiences that teach us both how the world works and how it might work better. In a technical sense, classroom education in the US has always had competing motivations. Compulsory public education was partially driven in the United States to create a more capable electorate, but it was also designed to create better workers. Later on, it served as a means to assimilate large immigrant populations that arrived in the late 18th and early 18th century. At its best, it created a shared experience that promoted essential skills and shared civic values that crossed class lines. At its worst, it propagated damaging state policies like segregation. We see those same tensions at work today. As battles in school boards across the nation show, the role of schools in reinforcing civil values is a matter of fierce disagreement. Book banning, creationism, and Critical Race Theory have taken turns as hot button topics in school curricula. Anti-racists like to say that hatred is learned. I’m not sure that’s entirely true. Our evolutionary survival instincts mark us with an instinctual fear of the other. But if it is true, then it’s also true that acceptance is learned. I note in the book that history is meant to educate us, not to comfort us. An honest education is our best medicine against hate and bigotry. But a dishonest one is worse than no education at all.

Can you please give us your favorite “Life Lesson Quote”? Can you share how that was relevant to you in your life?

I’ve always been suspicious of aphorism. Ironically, if I had to pick one it would be one of the corniest of them all: you miss 100% of the shots you don’t take. I wish I would have heeded it more in my life. I learned a bit late in the game that one way life is not analogous to sport is that your performance isn’t measured by your success percentage. In life, one homerun balances a thousand strikeouts, so you might as well keep swinging.

Is there a person in the world, or in the US with whom you would like to have a private breakfast or lunch with, and why? He or she might just see this, especially if we tag them. 🙂

As regards this topic, I could think of no better guide than Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr. In his contributions to both scholarship and popular culture, he has done invaluable work to frame the African-American experience as an essential part of the shared American experience. His work looks ugly facts in the eye, while still being able to point out the beauty. Hearing his firsthand perspective on his views of our history and on our future would be an education in the best sense.

How can our readers further follow your work online?

I’ll be sharing new ideas and developments as they happen on https://www.confessionsaview.com/

This was very meaningful, thank you so much. We wish you only continued success in your important work!

About The Interviewer: David Leichner is a veteran of the Israeli high-tech industry with significant experience in the areas of cyber and security, enterprise software and communications. At Cybellum, a leading provider of Product Security Lifecycle Management, David is responsible for creating and executing the marketing strategy and managing the global marketing team that forms the foundation for Cybellum’s product and market penetration. Prior to Cybellum, David was CMO at SQream and VP Sales and Marketing at endpoint protection vendor, Cynet. David is a member of the Board of Trustees of the Jerusalem Technology College. He holds a BA in Information Systems Management and an MBA in International Business from the City University of New York.

Upstanders: How Donald Blair Is Standing Up Against Antisemitism, Racism, Bigotry, and Hate was originally published in Authority Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.