There’s no such thing as writing a book that everyone likes! Not sure where I got that assumption from, given how often I skim through options on Netflix and toss down the remote in exasperation because there was “nothing interesting to watch”.

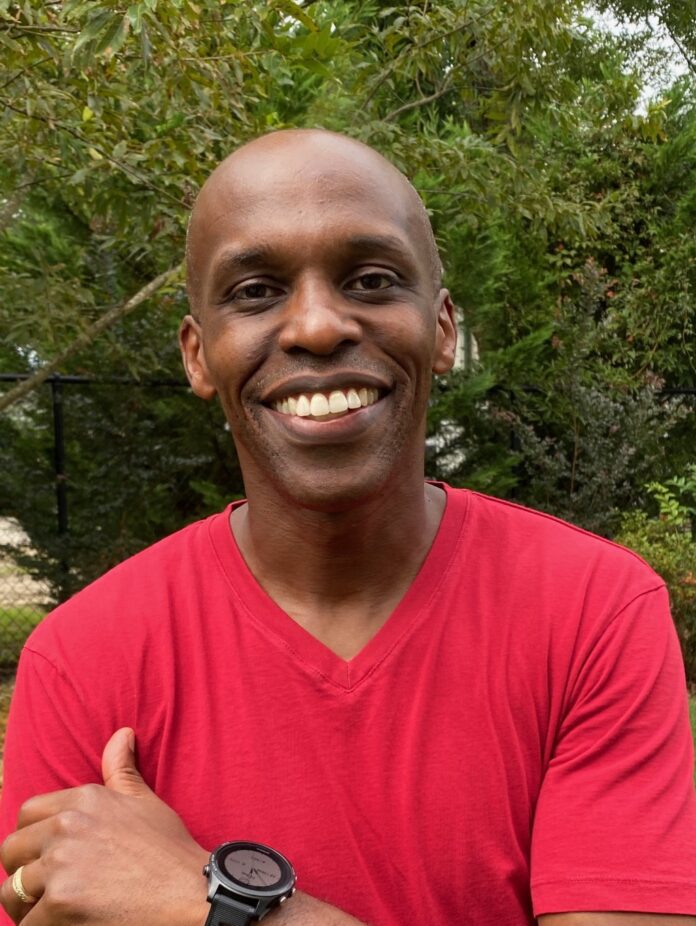

As part of my series about “authors who are making an important social impact”, I had the pleasure of interviewing Ndirangu Githaiga.

Ndirangu Githaiga is a Kenyan American novelist and physician. His first book, “The People of Ostrich Mountain”, published in 2020, won critical acclaim and was ranked among the Best Books of 2020 by Kirkus Reviews. Ndirangu believes that rich, multidimensional stories go a long way toward educating the world and dispelling unhelpful half-truths and stereotypes about Africa that persist to this day.

Thank you so much for joining us in this interview series! Before we dive into the main focus of our interview, our readers would love to “get to know you” a bit better. Can you tell us a bit about your childhood backstory?

I grew up in a middle-class household in Nairobi and spent most of my playtime outdoors. In the late seventies and early eighties there was only one TV station with transmission from 5.00 pm to 11.00 pm on weekdays with limited offerings for kids, so swinging on trees, firing catapults and throwing mudballs at each other was what my friends and I did for fun. My mother taught literature and we were surrounded by books from African authors like Chinua Achebe and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o as well as English authors like Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy and the Bronte sisters.

I enjoyed writing fictional essays in high school, but after I was accepted to the university to study medicine there didn’t seem to be a path forward for my writing. I wrote a couple of manuscripts in the early years of medical school — using a manual typewriter and whiteout, I should add — though these were not published. As school got busier, I set my writing aside though I always planned to come back to it. In 2018 — twenty-three years later — when my life as a physician settled down to a predictable pace I began working on “The People of Ostrich Mountain”, my first novel.

When you were younger, was there a book that you read that inspired you to take action or changed your life? Can you share a story about that?

As a boy of about six or seven, I read a children’s book by an author named Kenneth Mahood titled “Why are there more questions than answers, Grandad?”. It was a story about an orphan boy named Sandy who lived with his grandfather and drove him crazy by asking a never-ending stream of ridiculous questions until he was sent to the attic as punishment. There, an exciting world began to unfold before him with scenes marked by colorful memorable sentences such as, “Foolish forgetful firemen frequently flood filthy floors,” and “Beastly belligerent boys bemuddle beneficient birds!”. So enamored was I by the catchy lyrics and the vivid imagery that forty years later I purchased a worn copy of the book on Amazon, long out of print, that had been discarded by a library in Wells, Minnesota. That book, which I own to this day, taught me the magic of words which, like brushstrokes, can be used to create enduring impressions in the minds of the readers.

It has been said that our mistakes can be our greatest teachers. Can you share a story about the funniest mistake you made when you were first starting? Can you tell us what lesson you learned from that?

It seems ridiculous in hindsight that when I started out as an indie writer, I assumed that the minute I uploaded my first manuscript onto Amazon and hit “publish” the whole world would swarm in eagerly, wanting to read my novel. There was excitement among my friends and family for the first few months but for a while thereafter all I heard were crickets. Then readers started trickling in and the numbers grew with time, but I still chuckle when I remember the naive assumption I had in the beginning. It takes time to build a name as a writer and the old adage that a watched pot never boils rings true in this industry.

Can you describe how you aim to make a significant social impact with your book?

As kids growing up in Kenya, we read many books by English authors, such as the Famous Five series by Enid Blyton. While the stories were very engaging, we always felt like we were on the outside looking in, because they described the adventures of English kids who didn’t look like us, had different life experiences and talked about places unfamiliar to us. From this I learnt that if you don’t see yourself in the story and are always on the outside looking in, you inevitably begin to see your life and story as less important than those of others. I hope that my books will communicate to people of the African continent and diaspora that their stories matter. I would also like my novels to show the stories of Africa and her descendants to the world in a much more balanced and nuanced light than the superficial doom and gloom narratives that we come across all too often.

Can you share with us the most interesting story that you shared in your book?

During the colonial period in Kenya the police often conducted raids in the middle of the night, kicking down doors and forcing entire households out of their huts as they searched for suspected Mau Mau sympathizers. The scenes frequently involved terrified women and screaming children, many of whom were too young to understand what was going on. In one such instance, Inspector Wilcox and his two African constables are at Mũthee Karanja’s household and Karanja’s second wife and her children are kneeling timidly outside their hut with a menacing Alsatian straining feverishly at its leash and snarling at them. The old man (Mũthee Karanja) totters down the slope from his hut and calls out to the officers. When Nguru, one of the constables, yells to him to come at once to join his kneeling family he calmly disregards the order. Furious, Wilcox releases his grip on the dog which lunges toward the Karanja, growling threateningly, till it gets close to him and then inexplicably lies down at his feet with a docile whimper. The dog ignores the summons of an embarrassed Wilcox until Karanja gently whispers to it to go back. Frightened and bewildered, Wilcox and his sidekicks make up an excuse to move on to the next household. But there is more trouble in store the following day for the obnoxious Nguru because Karanja has an unusual ability to communicate with animals and has arranged an unpleasant surprise that turns his morning walk to work into a nightmare.

The novel is mostly about ordinary experiences. Mũthee Karanja’s story, however, is based on the life of the legendary Gĩkũyũ mystic Mũgo wa Kĩbirũ who, many years before the British arrived and started building a railway across Kenya, described a disquieting vision of a large shiny snake with smoke rising from its head out of whose mouth emerged people with a complexion as pale as the kĩengere frog and who carried sticks that produced fire which could kill when pointed at someone.

What was the “aha moment” or series of events that made you decide to bring your message to the greater world? Can you share a story about that?

In the more than two decades that I’ve lived in America, I’ve often been asked questions about Africa that revealed a limited understanding of what day-to day-life is for people in the continent. Most narratives in the West are unidimensional, based on primarily negative news stories about war, disease and poverty which often overlook the grace and resilience of its citizens, the beauty of communities where everyone comes together in good times and bad times, the fabulous weather (in Nairobi) and the occasional comical contradictions such as traffic coming to a halt because a pride of lions has wandered out of Nairobi National Park and decided to lie down to warm themselves on the tarmac.

Without sharing specific names, can you tell us a story about a particular individual who was impacted or helped by your cause?

My first book, “The People of Ostrich Mountain” was based on the Mau Mau war of independence which took place in the 1950s. Most of what I know about that time was what I heard from my parents and their generation. I felt validated when the folks in that age group read the book and identified with scenes in it, joyously recounting stories from their childhood such as taking the train across the country to boarding school without an accompanying adult, and wearing their first pair of shoes as adults. One friend of my dad’s told me how he was a scout for the Mau Mau as a boy — they would run through the village singing songs with coded messages to warn everyone that the colonial police was approaching the village. That same man later went to university in England to study engineering and had fond memories of one of his former high school teachers who hosted him and took care of him throughout the time he was in England. Now retired after an incredibly successful career, he was proud of the part he played as a boy in the armed rebellion that finally brought down the Union Jack in Kenya. But this did not prevent him from seeing the humanity of his British teacher and making a lasting personal connection with him.

Are there three things the community/society/politicians can do to help you address the root of the problem you are trying to solve?

- The media mantra of “If it bleeds it leads” which describes the profitability of bad news has been mostly harmful to Africa, perpetuating unhelpful racial stereotypes because nobody feels it worth their time to tell a complete, nuanced story. When people hear about gun violence in America, they are able to see this unfortunate social trend in the context of a multiplicity of narratives about this great nation rather than as a singular, defining caricature.

- Seek out multicultural content in books, movies etc. or better still, travel. There is a Gĩkũyũ proverb — Gĩkũyũ is the community I come from — that says “To travel is to become wise”. When we travel, we broaden our outlook and learn things from other cultures. Reading a book is an easy way to travel across the world or back in time to learn something new.

- Tell your story. During my American citizenship ceremony, the judge addressed us and said something profound which I would paraphrase thus: “You have all come from different places. America welcomes you. Bring the richness of the culture you come from and make it part of the American experience — don’t leave it behind.”

How do you define “Leadership”? Can you explain what you mean or give an example?

Leadership is seeing something around you that needs to change even when others don’t necessarily see it and using your unique perspective and God-given abilities to try to make things better.

Examples of this would be Sidney Poitier and Cicely Tyson who both refused to be cast in roles they felt would be demeaning to Black people, not without risk to their careers.

What are your “5 things I wish someone told me when I first started” and why? Please share a story or example for each.

#1: There’s no such thing as writing a book that everyone likes! Not sure where I got that assumption from, given how often I skim through options on Netflix and toss down the remote in exasperation because there was “nothing interesting to watch”. Part of maturing as a writer is understanding that art is subjective and there will be some people who enjoy your work and others who don’t.

#2: Things tend to move slowly in the world of the arts and as an artist you have to be content to put out your material and hope the world appreciates it, even if it takes years. Vincent van Gogh died poor, having only sold one painting in his lifetime; it took America decades to warm up to him even as his work gained traction in Europe, with his first painting being sold in the US thirty-two years after his death.

#3: If a friend tells you they bought your book, don’t stalk them two weeks later to find out what they thought about it. They probably have other things going on so they might not get to it as quickly as you think they should, so give them some space. It takes me several months to get to a book or movie on my list so I shouldn’t have a problem extending the same courtesy to others.

#4: Being an author is only one facet of your identity and hopefully not your entire raison d’être. Enjoy those friends who have trouble understanding why anyone would read for pleasure or might not be interested in your writing genre. While some of your friends may become fans and vice versa, the two circles don’t have to overlap.

#5: If you have a relatively successful debut novel, your subsequent books will always be measured against your first one, which can sometimes be overwhelming. One way to avoid feeling this pressure is never to write again and leave the world guessing what amazing work you were holding back or keep writing and allow the world to judge you on the totality of your work. As an artist enjoy the freedom of writing about the things that move you rather than feeling compelled to write an uninspired sequel to a storyline that resonated with readers.

YouTube Link: https://youtu.be/etwq7EVbsjo

Can you please give us your favorite “Life Lesson Quote”? Can you share how that was relevant to you in your life?

“Do what you feel in your heart to be right — for you’ll be criticized anyway.” This quote, attributed to Eleanor Roosevelt, is a useful one to have as a writer because there’s no shortage of critical reviews or people who read your books but are unable to connect with your vision and purpose.

Is there a person in the world, or in the US with whom you would like to have a private breakfast or lunch with, and why? He or she might just see this, especially if we tag them. 🙂

Denzel Washington. Like Sidney Poitier and Cicely Tyson who went ahead of him, his acting roles as a Black person reflect poise and dignity, making him an inspiration not just to Black people but people of all races.

How can our readers further follow your work online?

Visit my website at www.ndirangugithaiga.com or follow me on the social media links on my website.

This was very meaningful, thank you so much. We wish you only continued success on your great work!

Social Impact Authors: How & Why Author Ndirangu Githaiga Is Helping To Change Our World was originally published in Authority Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.