An Interview With Edward Sylvan

The primary impacts of Carbon Trace Productions are right there in our dual non-profit mission: documentary education and humanitarian service. We help students learn to make documentary films and we have them help our pro staff with our professional films. It’s pretty cool to see the lights go on for film majors and journalism majors when they discover what an important non-fiction medium this is. I have two journalism majors right now who are seriously re-working their professional expectations and desires based on their experiences making documentary films with Carbon Trace.

So, the first best answer to this question is: Carbon Trace is inspiring a new generation of documentary filmmakers to go do good in the world telling important stories that need to be told — not just the stories that can be sold. These skills can be put to use in many ways — not just the making of standard documentary films.

The causes we’re working on now include homelessness as I mentioned before. We’re also working on a sequel to Witness At Tornillo examining the lives of refugees stuck in the camp at Matamoros, Mexico, because of the “remain in Mexico” policy. Production on that got cut short 11 months ago just as we were heading back to the Matamoros for the second round of filming. The coronavirus stopped us cold. We hope to return sometime in the next few months to finish filming a family that we began following in January 2020 — a husband, wife and three small children. They’re still in the camp, still waiting for justice and opportunity. Now that the administration has changed in Washington, they are more hopeful than they have been. But the road to freedom is still blocked.

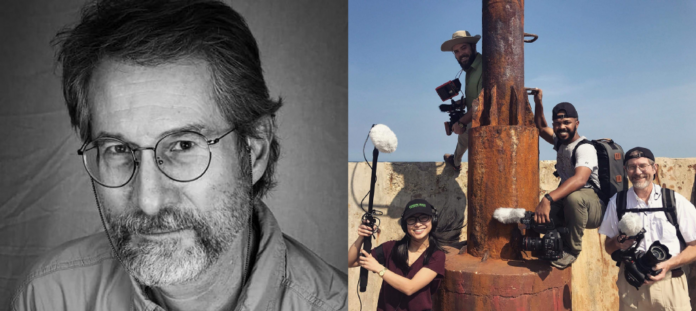

As a part of our series about “Filmmakers Making A Social Impact,” I had the pleasure of interviewing Dr. Andy Cline.

Dr. Andy Cline is a documentary filmmaker and professor of media, journalism and film at Missouri State University in Springfield. He is co-founder of Carbon Trace Productions, a non-profit documentary film studio with a dual mission: documentary education and humanitarian service. He and his students have completed 11 films, including four prize winners, since 2014.

Thank you so much for doing this interview with us! Before we dive in, our readers would love to get to know you a bit. Can you share your “backstory” that brought you to this career?

I began my career as a photojournalist, so telling visual stories has always been my focus. But I got into documentary filmmaking in part because I was avoiding writing a book.

I’d long been interested in new urbanism and the migration of baby boomers back to cities. At the time I began my first film in 2014, my wife and I had been living in a downtown loft for a year or so. I had intended to write a book about this topic. Well, one afternoon, sitting at an outdoor cafe in the heart of downtown Springfield, enjoying a beer, my wife said to me: “I notice you’re not getting after that book.”

Well, she was right. What she understands well about me is this: If I’m really interested in something, I get after it.

I told her I had lost interest in writing a book. Instead, I wanted to make a documentary film. To that point, I had never produced a video much over 90 seconds for news. She is always very encouraging and responded with: “Well, then make a movie.”

So, I asked some of my students to help me. This turned out to be the best move I ever made. I set out three goals. First, I wanted to make a film that didn’t suck. I had a colleague ask me what I hoped to achieve — seeing as how I was working outside my normal discipline — and I told him I wanted to achieve mediocre. To clarify, I intended to make a feature-length film rather than start with a shorter film, which was his advice. I’m a big believer in doing the thing you’re trying to learn. If you want to learn how to make a feature film, make a feature film.

Second, I wanted our film — Downtown: A New American Dream — to be accepted at the New Urbanism Film Festival in Los Angeles (it’s now the Better Cities Film Festival).

And third, I wanted to win something.

Well, we finished the film. It screened at the festival. And we won a category award. Boom! Done!

We had an after-party upon returning to Springfield. It had not occurred to me that I might make another film. I achieved everything I was after — including, by the way, mediocrity. But one of the students asked: “What’s next”? They all stared at me waiting for an answer. I had no answer. What I had was a handful of students who had achieved something important to them looking to me for continued leadership. And another project.

So here we are today. Something I’m very proud of: The original five students who helped me make Downtown still work with Carbon Trace Productions today. Two are employees — the executive director and the creative director. One is a member of the board of directors. The other two are frequent contractors and, to our great fortune, occasionally volunteers.

Can you share the funniest or most interesting story that occurred to you in the course of your filmmaking career?

Depending upon how hilarious you think stupid mistakes are, I can bend your ear for hours. We’ve had a series of dumb mistakes of a kind that make you wonder if documentary filmmaking is really what you should be doing. For example, there’s the time our field audio engineer — a student — fell asleep in the background of a formal interview and no one caught it until we cataloged the footage. I mean, that’s a whole lot of dumb.

But, on the other hand, there’s a story I tell that I think indicates how important it is to trust your team. So, I guess this is the “interesting” story.

In 2017, my team and I filmed a medical mission by the Syrian American Medical Society to the refugee camps in Jordan. We were providing them footage (our humanitarian mission) and working on our own documentary about the mental health crisis in Syrian refugee children. That film, by the way, is in post-production now.

The first day was spent in a dusty little frontier village within sight of the Syrian border. It was madness. The doctors were immediately overwhelmed with refugees in serious need. They were working in conditions that Westerners would find utterly shocking. And we could hardly make choices about what to film — what to focus on — in the midst of the crushing need of families seeking medical care. We were surrounded by desperation and pain. It felt like drowning.

All of us had worked together on Downtown and a few smaller projects that followed. We trusted each other. We respected each other. We had each other’s backs. And it was that trust that helped us get past those first, chaotic couple of hours.

Settling down to an extent that lets you focus on what’s important is a skill that had not been put to the test until this point with this team. It’s one thing to conduct standard interviews and shoot b-roll in your hometown. It’s quite another to drop yourself into the middle of a humanitarian crisis and expect to just do your job the same way. We were there to tell the story of “human devastation syndrome” as it affects Syrian refugee children. Think of it as a more dangerous form of post-traumatic stress disorder. It’s not yet a recognized medical diagnosis. Instead, it is an idea posited by Dr. Khalid Hamza, a professor, researcher and cognitive scientist at Lamar University in Texas. We had a team huddle in the chaos — each of us with our heads swimming in the madness of it all — and basically reminded ourselves to focus on the story, focus on the kids.

Who are some of the most interesting people you have interacted with? What was that like? Do you have any stories?

In June 2018, Shane Franklin and I went to Texas to participate in the protests over separating refugee children from their families at the border. Shane is the creative director of Carbon Trace Productions and one of the founders and original crew members. We took our cameras because that’s what we do. But we were not expecting much to come from it in terms of a project. We were there to protest. And protests are usually not that interesting. I spent about a year working as a photojournalist in Washington D.C. in the early 80s. Trust me, protests get old fast.

We met a friend of a friend who turned out to be an intriguing guy. His name is Joshua Rubin from Brooklyn, New York. We spent a few days with him protesting first in Brownsville then in El Paso. One of his goals was to go to the Tornillo internment camp outside of El Paso to protest. The day we went, we were the only ones there. Josh stood around with his sign, and we filmed him.

Later, we conducted a typical natural light hotel room interview with him. In other words, we weren’t trying very hard because no story was emerging. Josh, however, was an interesting interview and had some profound things to say about his experience as a protester and what he saw as the great struggle of the moment. Then he said: “I have to go home. It hurts to go home. I’m going to feel guilty flying out of here. Even though I don’t know if I’m doing any good … there’s a whole lifetime of struggle going on down here … I don’t know how to sit still. I don’t know how to not do something. I guess I’ll learn. If I don’t learn, I guess I’ll end up back here.”

Shane and I shared a look that said: That’s a story if he does. And he did. A few months later, he showed up at Tornillo with an RV and began a one-man vigil that grew into a movement. Our film, Witness At Tornillo, released in 2019, played in more than 30 cities and won a best documentary feature at the Kansas City FilmFest 2020.

Another interesting person is Dr. Tarif Bakdash. We worked with him on the Syrian documentary — still don’t have a title yet. He was our first contact with the Syrian American Medical Society. I discovered him because the head of the English department at Missouri State had recently written a biography and suggested him to me as a good documentary subject.

At the time, Dr. Bakdash was working in Jackson, Mississippi, as a pediatric neurologist. He also helps teach Syrian medical students over internet live feeds, and we got to witness him in action. Many of these students have had their educations interrupted by the war, yet they are also on the front lines treating injured civilians in makeshift hospitals tucked away in caves and the basements of bombed-out buildings. It was fascinating watching him discuss medicine over a live feed with a person in Syria obviously hunkered down in a bunker of some kind. That’s dedication.

What are some of the most interesting or exciting projects you are working on now?

We just finished A Vietnam Peace Story, which is the story of the journey — both the physical trip and the inner journey — back to Vietnam for a group of Marines who fought an early and devastating battle on Hill 50 in Quang Nai Province in March 1966. What I wanted to capture is the mental and emotional progression from Vietnam as war to Vietnam as place and people. I believe I succeeded.

Following our successful student film from last year, Songs From the Street, about the homeless members of the Springfield Street Choir, we’re continuing our focus locally on homelessness with a new project we’re calling All of a Sudden. It’s a character-driven story about the housing-first model of helping the homeless.

Housing first is the idea that before other types of help and programming for the chronically homeless will work, you first have to get a roof over their heads. Springfield has a successful example of this in Eden Village — a tiny home community specifically providing homes for the homeless.

The title comes from a quote by one of the residents. Just because you get a roof over a head doesn’t mean life is instantly wonderful again. She asked the question: All of a sudden, I’m supposed to be normal? So, our film is a personal look at the ongoing struggles — mental health, social, economic — even after shelter has been secured.

Our student film for the current school year is called 16 Weeks. It’s the story of the fall semester in the time of COVID-19. The cool thing about it is that the entire film is a story told vlog-style by many student participants — all of them sharing their daily lives and struggles as they negotiate college and COVID. We’ll release it this spring.

Which people in history inspire you the most? Why?

Jacob Riis hits all of the hot buttons for me. He was a journalist, a photographer, an author and an urban social reformer. There are several things about him I admire, but the best way to sum it all up is that his work exposing the wretched conditions of slum life in New York City in the late 1800s actually made a difference. Powerful people listened — Theodore Roosevelt arguably primary among them.

Questions such as this, I think, sometimes encourage people to grasp for the big name among the politically or religiously powerful. And, obviously, powerful people can and do have significant positive impacts on society.

But it’s people such as Jacob who really dig into the stories of the lives of people who should matter but often don’t. And he produced work that moved the politically powerful to action.

I want to do that — even in a small way. So at Carbon Trace, we tend to focus on telling such stories — whether it’s the story of the “subversive act of seeing” from Witness At Tornillo, or the unimaginable mental harm of the war on Syrian refugee children, or the need to just get a roof over a homeless person’s head.

Jacob understood his moment in history. He didn’t luck into it.

Let’s now shift to the main focus of our interview, how are you using your success to bring goodness to the world? Can you share with us the meaningful or exciting social impact causes you are working on right now?

The primary impacts of Carbon Trace Productions are right there in our dual non-profit mission: documentary education and humanitarian service. We help students learn to make documentary films and we have them help our pro staff with our professional films. It’s pretty cool to see the lights go on for film majors and journalism majors when they discover what an important non-fiction medium this is. I have two journalism majors right now who are seriously re-working their professional expectations and desires based on their experiences making documentary films with Carbon Trace.

So, the first best answer to this question is: Carbon Trace is inspiring a new generation of documentary filmmakers to go do good in the world telling important stories that need to be told — not just the stories that can be sold.

These skills can be put to use in many ways — not just the making of standard documentary films.

The causes we’re working on now include homelessness as I mentioned before. We’re also working on a sequel to Witness At Tornillo examining the lives of refugees stuck in the camp at Matamoros, Mexico, because of the “remain in Mexico” policy. Production on that got cut short 11 months ago just as we were heading back to the Matamoros for a second round of filming. The coronavirus stopped us cold. We hope to return sometime in the next few months to finish filming a family that we began following in January 2020 — a husband, wife and three small children. They’re still in the camp, still waiting for justice and opportunity. Now that the administration has changed in Washington, they are more hopeful than they have been. But the road to freedom is still blocked.

Many of us have ideas, dreams and passions, but never manifest it. But you did. Was there an “Aha Moment” that made you decide that you were actually going to step up and take action for this cause? What was that final trigger?

Aha moments for me generally revolve around discovering stories.

So the founding aha moment was Dr. W.D. Blackmon, head of English department at Missouri State, handing me his book about Dr. Tarif Bakdash and suggesting him as a good documentary subject. The guy is a good story in his own right, including having known Bashar al-Assad, the Syrian dictator, in medical school and having worked for his regime before fleeing Syria.

Our first film — Downtown — wasn’t story-based. It’s just relentless reporting about an issue — hence its mediocrity.

But as soon as I started reading Dr. Blackmon’s book, well, my eyes opened to the possibilities. I was also looking for something else to do since I had students eager to keep making documentaries. I was also motivated by the idea that I might actually be able to make something a little better than mediocre.

Story is the thing.

So, at each step of the way since then, everything I have done with Carbon Trace, has been about finding and telling stories that need to be told whether or not money can be made in the telling.

Can you tell us a story about a particular individual who was impacted or helped by your cause?

I wonder sometimes about how much direct help a documentary film can be for the subjects of a film. We haven’t solved much of anything. But that’s not our purpose. The telling of these stories is more about making others aware in the hopes that they might then do something impactful.

A movement grew up around Joshua Rubin’s protesting of children separated from their families and put in internment camps. Our film helped the witness movement along its way by telling Josh’s story. It’s the story of what one man can do. It’s not the story of what a documentary film crew can do. No one who sees the film cares about us. They care about the kids and Josh’s “subversive act of seeing” aimed at getting the people responsible for the camps to question their morality. That’s an important point Josh makes that our film is centered on. Josh wasn’t helping these kids directly. He couldn’t. He had no power to do anything to get them released. But what he could do — the essence of the story we told — was the power of one person to make those involved think about their participation in an atrocity.

Songs From the Street didn’t help any homeless people. But it helped create a wider audience, and more donations, for the Springfield Street Choir.

A Vietnam Peace story did not help any vets process their experiences and come, perhaps, to closure. But it did show what it means to shift one’s perspective about Vietnam.

This question is best asked of that fellow who’s huddled with his family in Matamoros right now — Josué Rolando Cornejo Sabillon. After we finish the sequel — the working title is Witness at the Border — I wonder what he will say if someone asks him: Did that film help your cause? Did it make a difference in your life?

I wonder.

Are there three things that individuals, society or the government can do to support you in this effort?

First, because Carbon Trace Productions is a 501(c)3 non-profit that works with students, we can always use donations — big and small. We can accept cash, securities and stuff. If you have used cameras to donate — especially digital cinema cameras — I can help take them off your hands. I can help relieve you of just about any stray filmmaking equipment you have sitting around. And you get the tax deduction. Plus, the cool thing is our donors are part of the team. We include donors in our most important team communications. You get to be right there in the thick of it with us. And we listen to our donors. Songs From the Street, our award-winning student feature for 2020, originated from a suggestion by a donor. Helping Carbon Trace continue its work is an easy way to be involved in documentary filmmaking. And who doesn’t love a tax-deduction?

Second, tell us your story. You may be our next important project.

Third, hire Carbon Trace. If you have a documentary film you’d like to make — as long as it fits our mission — but you aren’t sure how to start, give us call. I think you’ll be happy with the cost/quality ratio we offer.

What are your “5 things I wish someone told me when I first started” and why. Please share a story or example for each.

● People will love your film — even if it’s mediocre. And their love of it will encourage them to try to take ownership of it. Not in a nefarious way. Not in terms of money. Instead, they’ll “help” you share it. They’ll share it when they shouldn’t. They’ll expect you to be happy that they set up a screening three states away without checking with you first. Posting it to Facebook? What? That doesn’t help you? We learned the hard way that you need to explain how the whole film distribution thing works — in our case, mostly the film festivals — as you’re starting a project, as you’re filming a project, as you’re editing a project and as you’re marketing a project. And for a while after that, too. The innocent desire to take over your film is one of the ways you know they love it. Just don’t let them love it to death.

● Audio is the most important technical thing. Your video can suck. Sometimes it’s better if the video sucks. But audio can never suck. Audiences will not forgive bad audio. I have my students watch White Helmets, the documentary about the guys who rescue people from bombed buildings in Syria. The guy who did most of the filming was a White Helmets crew member working with a DSLR. I give my students this thought experiment: Imagine what that film would be like if the photographer had a Steadicam and digital cinema camera. And I can see the lightbulbs go on as they realize the film would not be anywhere near as powerful if the video were perfect. But it wouldn’t have seen the light of day if the audio had been bad. Oh, and make sure your audio guy doesn’t fall asleep in the shot. That’s bad, too.

● I don’t have specific advice for this next one, except to be aware: Documentary films are supposed to be factual and true in a way very similar — although not identical — to journalism. We make choices that affect the truth of our films and how subjects and other stakeholders understand themselves in the stories we tell. We choose how to structure stories, how to represent the subjects and how to manipulate — yes, that’s the right word — the audience with music and editing. We wouldn’t be telling stories in the first place if we didn’t want the audience to think and/or feel particular things in regard to them.

● Once people know you’re a documentary filmmaker — and after you make your first film, that’s exactly what you are — they will bring you ideas. Listen to them. A guy called my department a couple of years ago to say he thought he’d be a good subject for a documentary film, which is exactly as hilarious as it sounds. The secretary passed him on to me with a chuckle. Well, I met the guy for coffee. I’ll listen to anyone’s story. As it turned out, his idea was a documentary about his last season as a losing high school basketball coach; the season before his team had won no games. The result was Zero, our student film that won the Award of Distinction for Feature Documentary Film at the Broadcast Education Association Festival of Arts last year. That’s an international competition.

● No one had to tell me that making money at this was going to be tough, so please yourself first. But, yeah, I needed someone to tell me — and someone finally did — that bringing in money somehow is about the only way you’ll be able to tell the stories you want to tell. There are many ways to accomplish this. I chose to go the non-profit route. Non-profit, by the way, doesn’t mean you don’t make money. It means you’re obligated to use the money you make in particular ways. We use it to fund filmmaking for students. Right now, we work almost exclusively with students at Missouri State. The five-year plan is to dramatically expand that.

If you could tell other young people one thing about why they should consider making a positive impact on our environment or society, like you, what would you tell them?

The world’s books of quotations are filled with sayings about getting involved in things greater than yourself and dedicating yourself to making lives better or the world better. I’m not even going to try to say this in some kind of memorable way. There’s a reason so many quotes like that exist. It’s because those ideas are true given that we are social creatures skilled in cooperation and empathy. Happiness is found in making things better. Maybe not money. Maybe not fame. But then no one needs those. What we need is to be helpful.

We are very blessed that many other Social Impact Heroes read this column. Is there a person in the world, or in the US, whom you would like to collaborate with, and why? He or she might see this. 🙂

Not so much a person as an organization. I went to the World’s Fair in New York City with my family in 1964. I was just a little kid. Two things stuck with me. The Disney pavilion had a ride where performers — or maybe it was robots? — sang “It’s A Small World After All.” And I also got to see, and hear my dad talk about, the United Nations. Those two things morphed in my mind and made me very interested in the United Nations, where, I assumed, everyone sang that song everyday while trying to make the world better. Oh, and I was a big fan of the Man From U.N.C.L.E. TV show. I was hooked.

I’ve often wondered why I never tried to get involved there or get a job there later in life. But every time I go to New York, I like to visit the UN. And I’ve walked around that place wondering, “Why am I not working here?”

Perhaps I’m destined to do some documentary work for them — maybe for the UN High Commission on Refugees, since telling the stories of refugees has been important for Carbon Trace in the past few years.

So, if High Commissioner Filippo Grandi is reading this, let me just say: Give me a call. Carbon Trace is ready to go anywhere in the world where people are struggling to find safety so we can tell their stories and/or not let their stories be forgotten.

I promise I won’t sing It’s a Small World!

Can you please give us your favorite “Life Lesson Quote”? Can you share how that was relevant to you in your life?

The book that had the most impact on my life (it encouraged me to become an academic) is Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Pirsig. There’s a quote by the main character — who is Pirsig himself fictionalized — that says: “The cutting edge of this moment right here and now is always nothing less than the totality of everything there is.”

Among the many things I take from that is: Be good. Do good. Encourage good. Because this moment, the very moment that I’m saying this to you, the very moment the audience is reading these words, is the entirety of the world. What choices are you making? Make them good. Well, except for my first film which was decidedly mediocre, but it was the best I could do at the time. So, yeah, the quote, I think, allows for, encourages really, all of us to try hard because this moment right here and now is everything. I think about the moment my wife said to me, “Well, then make a movie.”

How can our readers follow you online?

First, follow Carbon Trace Productions. Start with the website at carbontrace.org. There are Facebook pages for all of our films. Twitter, too. I can be found on Twitter @arcline and Instagram @acline. And I’m doing the Substack newsletter thing at docfilm.substack.com. If all else fails, it’s easy to find me on the Missouri State University website.

This was great, thank you so much for sharing your story and doing this with us. We wish you continued success!

About The Interviewer: Growing up in Canada, Edward Sylvan was an unlikely candidate to make a mark on the high-powered film industry based in Hollywood. But as CEO of Sycamore Entertainment Group Inc, (SEGI) Sylvan is among a select group of less than ten Black executives who have founded, own and control a publicly traded company. Now, deeply involved in the movie business, he is providing opportunities for people of color.

In 2020, he was appointed president of the Monaco International Film Festival, and was encouraged to take the festival in a new digital direction.

Raised in Toronto, he attended York University where he studied Economics and Political Science, then went to work in finance on Bay Street, (the city’s equivalent of Wall Street). After years of handling equities trading, film tax credits, options trading and mergers and acquisitions for the film, mining and technology industries, in 2008 he decided to reorient his career fully towards the entertainment business.

With the aim of helping Los Angeles filmmakers of color who were struggling to understand how to raise capital, Sylvan wanted to provide them with ways to finance their creative endeavors.

At Sycamore Entertainment he specializes in print and advertising financing, marketing, acquisition and worldwide distribution of quality feature-length motion pictures, and is concerned with acquiring, producing and promoting films about equality, diversity and other thought provoking subject matter which will also include nonviolent storytelling.

Filmmakers Making A Social Impact: Why & How Filmmaker Dr Andy Cline Is Helping To Change Our World was originally published in Authority Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.