An Interview With Ian Benke

Write from the heart. I never start a novel by asking who I’m writing for or what genre it fits into. Stories start as seeds in your brain and then flow out through your heart. If you try to force that seed to grow into something it’s not, you lose the soul of the book. It’s written based on analytics rather than what it’s destined to become. Maybe it will get published, maybe it won’t. But as long as you write from the heart, you will get what you need from the manuscript. In my opinion, writers should write for themselves. When they do, more often than not the story resonates with others. When you strip away our surface differences, we all have the same burning questions resonating down deep.

Science Fiction and Fantasy are hugely popular genres. What does it take for a writer today, to write compelling and successful Science Fiction and Fantasy stories? Authority Magazine started a new series called “How To Write Compelling Science Fiction and Fantasy Stories”. In this series we are talking to anyone who is a Science Fiction or Fantasy author, or an authority or expert on how to write compelling Science Fiction and Fantasy .

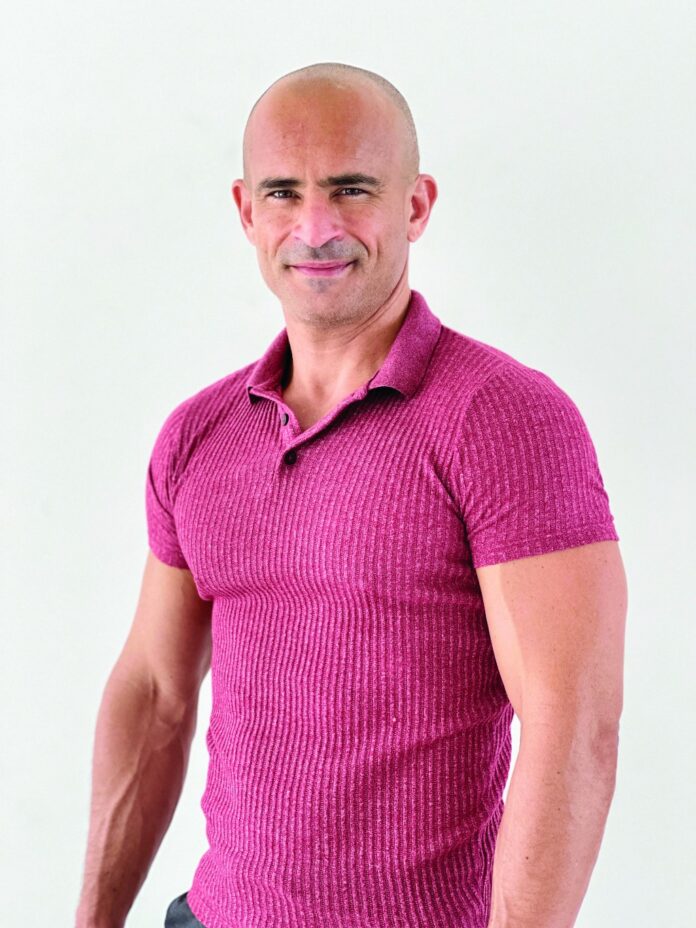

As a part of this series, I had the pleasure of interviewing Erich Krauss.

Erich Krauss is a New York Times bestselling author and has written more than thirty books. For more than two decades he traveled the globe searching for inspiration for his writing, including fighting professionally in Muay Thai bouts in Thailand, living with an Indian tribe deep in the Amazon, hang gliding throughout Central America, and bicycling across the United States and Canada. While writing on the road, he dreamed up a new publishing model where author and publisher work closely together to bring the best possible books to market. In 2006 he created Victory Belt Publishing and applied this model, which quickly led to a host of runaway New York Times and international bestsellers. After more than fifteen years as president and publisher of Victory Belt, Krauss took a step back in 2020 to revisit his passion — writing fiction. Drawing from his world travels as well as the current global health crisis, he wrote Primitives, a post-apocalyptic thriller in the vein of two of his favorite novels, World WarZ and The Road.

Thank you so much for joining us in this interview series! Before we dive into the main focus of our interview, our readers would love to “get to know you” a bit better. Can you share a story about what first drew you to writing over other forms of storytelling?

For me, writing always seemed like the medium of storytelling that offered the most control. Your editor will certainly suggest edits to your manuscript, but it’s not like in filmmaking where your script can get pulled apart and reassembled to fit a specific demographic, ultimately having no resemblance to the original story. I toyed with writing when I was very young, but during my teenage years adventure always took center stage. I was an intern at a survival school in the deserts of Utah at the age of fourteen, teaching others how to build primitive shelters, make fire with sticks, and survive on bugs for weeks at a time. Then I spent my summers biking across the US, sleeping in the dirt and eating cans of beans. However, a few weeks before I graduated from college, it started to dawn on me that it might prove difficult to make “adventure” a career. I remember waking up one morning and thinking, “I’m going to be a writer.” I could still travel the world, but also (hopefully) make money doing so. A few months later, I filled a backpack with the bare essentials, gathered my minimal savings, and began a nine-year journey that took me from the Amazon to the Muay Thai rings of Thailand. In each location, I’d find the cheapest place I could — sometimes a shack without running water, sometimes a moldy hotel room — and spend hours writing, pulling from my surroundings. I must have written ten novels during this period, none of which ever saw the light of day. But it was a needed exercise to hone my chops. For the “making money” part, I discovered that there were countless intriguing stories that could be covered in these remote locations, and though it wasn’t what I truly wanted to be doing, I began publishing nonfiction books that allowed me to continue to write.

You are a successful author. Which three character traits do you think were most instrumental to your success? Can you please share a story or example for each?

Being adventurous, empathetic, and confident are the three traits that are most instrumental in my writing. With fiction, I realized early on that without unique experiences, it would be very difficult to make a novel stand out. While it is possible to fudge it from the comforts of home, it’s the small nuances that come from traveling the world that make your story credible. For example, several of my early novels take place in the Amazon. I spent months living with an Indian tribe in the jungle, and if I had to write about what their lives and culture were like without ever having been there, nothing would be accurate, and the reader would pick up on that. With a decade of travel under my belt, I realized that with each adventure, with each year that passed, my writing improved dramatically because I could draw from all those experiences, picking and choosing to form colorful settings and characters. Empathy ties directly in with that. Without it, it’s possible to travel the globe and never pick up a thing about what drives people who come from cultures distinctly different from your own. When you can tap into what fuels their souls, the puzzle pieces of their culture all fall into place. It’s those first two traits, being adventurous and empathic, that helped fuel my confidence. When you draw from real experiences, real people, a lot fewer stories end up in the trash bin. No matter how outlandish or fantastical a story might be, drawing from reality removes much of the doubt all writers face.

Can you tell us a bit about the interesting or exciting projects you are working on or wish to create? What are your goals for these projects?

Currently, I’m working on the next books in the Primitives saga. The story seems to get larger each day, and already I have a series planned that takes place hundreds of years after the Primitives storyline, forcing me to ask what future society might be like when built on the deranged ideals of a madman. As a writer, I can’t help but look at what society currently considers “normal” and wonder how that normalcy developed. Are the tenets of how humans should act and interact ingrained in our DNA, or did they develop from a concept formed in the distant past? And if so, how did that original concept get bent and twisted over the millennia? As with most writers, my ultimate goal is to see these stories carried over to the big screen.

Wonderful. Let’s now shift to the main focus of our interview. Let’s begin with a basic definition so that all of us are on the same page. How do you define sci-fi or fantasy? How is it different from speculative fiction?

I’ve never been big on defining what genre a book should be categorized in. Honestly, I never even researched the defining criteria for sci-fi, fantasy, or speculative fiction. With Primitives, early reviewers labeled it everything from post-apocalyptic to dystopian to fantasy. I didn’t have any of these in mind when I wrote the book. There was a story inside me, and I sat down and let it flow. I always figured the readers would let me know what type of book it was to them. I know there are writers who cater to a specific niche because they see a market there or their publisher wants that particular type of book, but to me, labels always stifle the creative process. I know they are important, mostly so readers can find the correct shelves in the bookstore, but I always felt those labels should be created by the publisher, not the writer. The writer’s job is to bring reality to a story, no matter how unrealistic the premise might be.

It seems that despite countless changes in media and communication technologies, novels and written fiction always survive, and as the rate of change increases with technology, written sci-fi becomes more popular. Why do you think that is?

The more technology evolves, the more our imaginations go stagnant. Need to fix your radiator? Google tells you how to do it, no thought needed. Wondering what’s going on around the globe? The news lets you know, attached with an opinion piece on how you should feel about it. For the longest time, we thought the brain we’re born with is the brain we carry throughout life, but then we discovered neuroplasticity. We have the ability to change and modify the function and structure of our brains throughout life, much of which can be accomplished by utilizing our imaginations. When you remove imagination from the equation, which is happening more and more in modern times, your brain can regress. Neural connections are broken. It’s something you can feel — like a missing piece in your soul — and as technology continues to remove thought from our daily lives, people are thirsting for an escape, a way to tap into neuroplasticity and feel themselves evolve. Reading fiction is perhaps the best way to accomplish this because even with the most well-written books, the reader must tap into their mind and paint a picture of their own. It forms new neural connections that can help them navigate their lives and emotions and connect with themselves.

In your opinion, what are the benefits to reading sci-fi, and how do they compare to watching sci-fi on film and television?

Sci-fi movies are a wonderful blast of colorful special effects and strange creatures, detailed down to the orange hairs sprouting from their ears. They can be a great escape from a difficult day and fill your dreams with adventure. But what you see is not your world. The characters are not your characters. A movie might ignite your imagination on what the future holds or how the storyline might continue, but nothing can tap into your creativity like a good sci-fi book. Even in the best novels, there are always missing pieces to the setting or characters, and the reader is forced to start filling in the gaps. This turns the reader into an artist and fulfills the primal human desire to create. When people talk about movies, it’s always, “Did you see that one scene…,” and identical images pop into both parties’ heads. Ask two people to discuss the same scene in a book, and nine times out of ten, the images generated in their minds are vastly different.

What authors and artists, dead or alive, inspired you to write?

Seeing that I’ve read the Gunslinger series more times than I can count, I’d have to say Stephen King has inspired me the most as a writer. I’ve analyzed nearly every sentence in his first book in the series — could even recite every line of the first five pages for a while there. Pure poetry.

If you could ask your favorite Science Fiction and Fantasy author a question, what would it be?

Instead of asking Stephen King a specific question, I would like to stick him in an MRI machine while he’s writing his books to see what sections of his brain light up. I’ve had experiences where I sit down in the morning to start writing, and when I look up it’s dark outside. I’ve somehow lost ten or eleven hours. Something tells me Stephen King has lost years. Maybe decades. Most humans only use twenty or so percent of their brain. I truly believe getting into the flow state — whether it be writing or building a birdhouse — is how we tap into the rest. Over the past thirty years, I’m sure Stephen King has felt much like an early explorer, cascading through the uncharted territory of the mind. It has to have been one hell of a ride.

We’d like to learn more about your writing. How would you describe yourself as an author? Can you please share a specific passage that you think exemplifies your style?

Writing is a way for me to try and answer questions floating around in my head. I’m deeply curious about nature, and I’ve spent considerable time studying topics most leave to others, such as immunology. We now know that inflammation is the cause of nearly every chronic disease, yet this is completely ignored by the modern medical establishment. Somehow, treating symptoms rather than root causes has been accepted by the public. How did this happen? And if we were to start over, would this play out in the same way? At times, our sense of normalcy — which should intuitively seem abnormal (maybe even insane) — builds frustration, and that frustration leads to a story that allows me to work through it. Tap into why we do what we do, as well as seek answers that might lie somewhere out there in the abyss. When the story is finished, it feels like a burden has been stripped away. For example, years ago I was backpacking through Central America and saw my first dead body lying on the side of the street. It had clearly been there for days, if not weeks, and people were walking past it as if it weren’t there. The body was still well enough intact to see that the man was of indigenous descent, and it pulled me into the racial conflict that had been raging on the isthmus for centuries. Just twenty-one years old, I couldn’t understand the hate and cruelty, and I attempted to sort through those messy thoughts through my writing. Below is the first paragraph from that book. Though I never attempted to publish it, putting the story on paper was highly therapeutic.

“It was the hottest and driest July in years. The blaze of sun had scorched the sewage flats on the outskirts of the city and easterly winds pulled thick clouds of fecal dust across town. Entire city blocks were freckled gray. But there were more grotesque smells, and certainly sights, that my daytime excursions forced me to bear. The bodies of Indian men and women who had not escaped before Government Forces cleansed the city months earlier lay bloated and gaseous in the sun. Starving dogs feasted on the corpses, and the mongrels that did not die from the spoiled meat grew plumper by the day as the death toll increased.“

Based on your own experience and success, what are the “Five Things You Need to Write Compelling Science Fiction and Fantasy Stories?” If you can, please share a story or example for each.

One: Pull from real-life experiences. Primitives follows two characters in a post-apocalyptic future, one of whom is living in the jungles of Costa Rica, and the other barely surviving in the Utah desert. I spent many summers in my youth teaching survival school in the Utah desert, and I know what it’s like to struggle there — the horseflies that take huge chunks out of your skin, the hours of laying figure-four traps to catch one measly rabbit for dinner, the bugs that crawl in your ears as you fight off the cold in a primitive shelter packed with leaves. When I was eighteen, I volunteered at Cabo Blanco National Park in Costa Rica. The ranger didn’t much like foreigners, so he put me on a boat and dropped me off at a scientific research center, which was just a shack without electricity, miles from civilization. I spent two weeks in complete isolation and went a little mad. I even stopped wearing clothes, as there were only the howler monkeys high in the trees. Well, one night I awoke and both my legs were wet. Lighting a candle, I saw the lower half of my body was covered in blood. There were deadly snakes out there, as well as scorpions six inches long. I was sure something large had come through the open door and fed on me in my sleep. Well, eventually I found a small hole in the top of my big toe, spouting blood. I became certain it had been a snake, even though no snakes were around. So, at first light, I put on my shoes and attempted to hike back to the ranger station along the cobblestone beach. Cliffs quickly rose to my left, and then the tide came in. A wave would knock me down, tumbling my body across the cobblestones, and when it went out, I would run fifty feet or so before the next wave hit me. With blood still leaking from my toe, I became certain the venom would kick in, I’d get washed out to sea, and the sharks would finish me. Luckily, before too long, I found a place where I could climb up the cliff. When I finally reached the ranger station, I was told I hadn’t been bitten by a snake, but rather a bat. A relief for certain, but the experience stuck in my mind. This is why I opened Sarah’s storyline along that same beach, her character filled with an equal amount of dread. If not for my time spent in these two locations — if not for the suffering I experienced there — I never would have had the confidence to write about them. In my opinion, a broad range of experiences is key to writing compelling science fiction.

Two: Question everything. In my opinion, the most compelling aspect of science fiction is that we can take problems from the real world and apply them to a strange new land, allowing us to distance ourselves from those problems and look at them through a lens we seldom use when viewing our own world. This is the backbone of any good sci-fi story, and it comes about by questioning everything. For example, in Primitives, a mad scientist regresses humanity to a primal state. Thirty years in the future, the main characters must look at humanity’s past flaws and decide if they should fight to help bring it back.

Three: Write from the heart. I never start a novel by asking who I’m writing for or what genre it fits into. Stories start as seeds in your brain and then flow out through your heart. If you try to force that seed to grow into something it’s not, you lose the soul of the book. It’s written based on analytics rather than what it’s destined to become. Maybe it will get published, maybe it won’t. But as long as you write from the heart, you will get what you need from the manuscript. In my opinion, writers should write for themselves. When they do, more often than not the story resonates with others. When you strip away our surface differences, we all have the same burning questions resonating down deep.

Four: Tap into your strengths and flaws. No one likes to read about characters who are perfect or completely imperfect. We all have flaws — writers maybe more than most — and by being honest with yourself and applying your deepest weaknesses to your characters, you can step away from the canned flaws of most villains and create characters everyone can relate to.

Five: Write day and night. Of course, there are writers who can sit down to write and bang out a perfect manuscript in the first go. That’s not the majority of us. At one point in my life, my friends called me Gollum. I was living in a moldy basement beneath a strip club, and for a year I only came up to use the restroom. My skin grew pasty white and I had permanent bags under my eyes. I must have started seven or eight novels in that time, some of which I got to near completion, but none of them were ever finished. At that point in my life, I had spent more than a decade training in the martial arts. I remember my first karate class at seven or eight years of age. I came home full of confidence, only to have a neighborhood kid mop my back deck with my face. So, I trained, and eventually I started fighting professionally in Thailand. But when I was down in that basement, I remembered that first fight. Remembered what it took to get where I wanted to go. With writing, we all think we should be able to get the perfect novel the first time. In my experience, that’s not how things work unless you’re one of the blessed, which is a rarity indeed. So write without expectations. Write for the joy of it. It’s okay to dream. I spent many of those nights in the basement dreaming of the day I would become a New York Times bestselling author. I didn’t put a time limit on achieving that goal, but I told myself it would happen before I died. And when that dream came true — after years of scrapping one novel after another — the reward was indescribable. Be patient, put in your time, and dream.

We are very blessed that some of the biggest names in Entertainment, Business, VC funding, and Sports read this column. Is there a person in the world, or in the US, with whom you would love to have a private breakfast or lunch, and why? He or she might just see this, especially if we both tag them 🙂

–I’d love to say I would pick some Nobel Laureate in medicine to have breakfast with. But as much as I’d enjoy that conversation, my first choice would be Charlie Day. I must have watched every episode of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia fifty times. When I was at my sickest with Lyme disease, barely able to get up off the couch, his humor in that show pulled me through. So, Charlie, if you’re reading this, a big heartfelt thank you. And if you ever decide to engage in another bare-knuckle fight, come to Las Vegas. Forrest Griffin is a good friend of mine, and I’m sure we can get you better prepared than Dennis did for the last one.

How can our readers further follow your work online?

Goodreads, Netgalley, Primitivesbook.com

Thank you for these excellent insights, and we greatly appreciate the time you spent. We wish you continued success.

About The Interviewer: Ian Benke is a multi-talented artist with a passion for written storytelling and static visual art — anything that can be printed on a page. Inspired by Mega Man, John Steinbeck, and commercials, I.B.’s science fiction writing and art explore the growing bond between technology and culture, imagining where it will lead and the people it will shape. He is the author of Future Fables and Strange Stories, the upcoming It’s Dangerous to Go Alone trilogy, and contributes to Pulp Kings. The CEO and Co-Founder of Stray Books, and an origami enthusiast, Ian is an advocate of independent, collaborative, and Canadian art. https://ibwordsandart.ca

Author Erich Krauss On How To Create Compelling Science Fiction and Fantasy Stories was originally published in Authority Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.