Putting The United Back Into The United States: Author Hajar Yazdiha On The 5 Things That Each Of Us Can Do To Help Unite Our Polarized Society

An Interview With Jake Frankel

Listen: Unity does not mean sameness, but we cannot know unity if we do not know the other. Knowing each other requires developing our practice of listening. Listening does not have to mean acquiescence or agreement. Rather, listening builds knowing and seeing, of one another, as humans. When we know and see, we can identify the common threads and where we might dismantle or build.

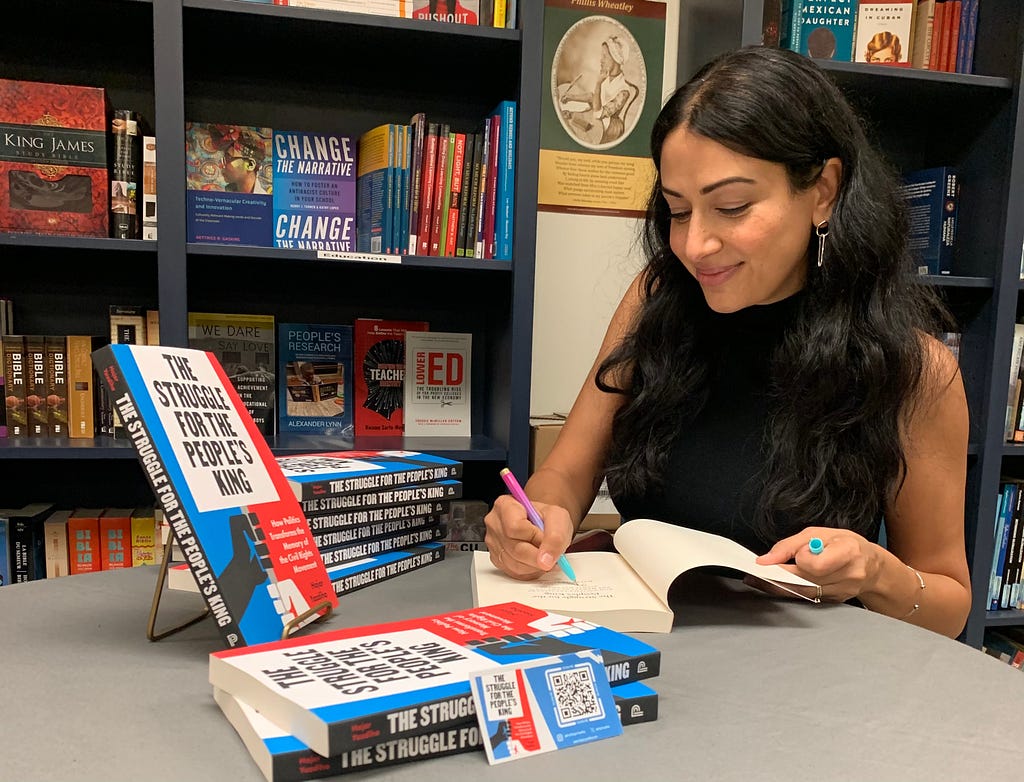

As a part of our series about 5 Things That Each Of Us Can Do To Help Unite Our Polarized Society, I had the pleasure of interviewing Professor Hajar Yazdiha.

Hajar Yazdiha is an Assistant Professor of Sociology, faculty affiliate of the Equity Research Institute, and a 2023–2025 CIFAR Global Azrieli Scholar. Dr. Yazdiha received her Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and is a former Ford Postdoctoral Fellow and Turpanjian Postdoctoral Fellow of the Chair in Civil Society and Social Change.

What are the social forces that bring us together and keep us apart? What does it take to feel like we belong, to a community and to one another? Hajar Yazdiha’s research shows how powerful institutions like law and media categorize groups into an “us” and a “them” and make the boundaries between us feel real and natural. She also shows how these categories matter for everyday people, the communities where we feel like we belong, and how this “groupness” shapes our identity, our politics, and even our imaginations of what type of society may be possible.

Dr. Yazdiha’s research examines these questions by analyzing the mechanisms underlying the politics of inclusion and exclusion. This work crosses subfields of race and ethnicity, migration, social movements, culture, and law using mixed methods including interview, survey, historical, and computational text analysis.

Dr. Yazdiha’s new book entitled, The Struggle for the People’s King: How Politics Transforms the Memory of the Civil Rights Movement (Princeton University Press) examines how a wide range of rivaling social movements across the political spectrum deploy competing interpretations of the Civil Rights Movement to make claims around national identity and inclusion. Comparing how rival movements constituted by minority and majority groups with a range of identities — racial, gender, sexuality, religious, moral, political — battle over collective memory, the book documents how the misuses of the racial past erode multicultural democracy.

This research provides new insights into the relationship between macro-level institutional structures, meso-level group processes of collective identity formation and collective behavior, and micro-level perceptions, emotions, and mental health. Through her research, Dr. Yazdiha works to understand how systems of inequality become entrenched and how groups develop strategies to resist, contest, and manifest alternative futures.

Thank you so much for joining us in this interview series! Before we dive into the main focus of our interview, our readers would love to “get to know you” a bit better. Can you tell us a bit about your childhood backstory?

I am the child of Iranian political refugees and technically am an immigrant myself since I was born in Germany, but I grew up in Northern Virginia in a community that was, at the time, predominantly white. I’ve come to find that a lot of my childhood experiences, of feeling like I was a perpetual outsider trying to fit in, of feeling both invisible and hypervisible at the same time, of feeling shame and embarrassment over everything from my frizzy hair to the way my house smelled to my parents’ accents, are experiences I share with a lot of children of immigrants growing up in the 1990’s. I’m so grateful there’s a common language for these experiences now!

What or who inspired you to pursue your career? We’d love to hear the story.

Since I was a kid I have loved sitting in a quiet room by myself, thinking and reading and writing and daydreaming. To that childhood question of what I wanted to be when I grew up, I always said some variation of a teacher or writer. And though I did well in school, I was never fully committed in the way some kids are who know exactly what they’re doing and where they’re going.

But in my senior year of highschool, I had an AP English teacher, Mr. McCabe, who saw something in me. He wrote personal notes to all of us at the end of the year, and I remember one line he wrote to me, “You are one of a handful of true academics. Speak up and use your voice.” It stuck with me. It would be another decade before I realized knowledge-production, being a professor, was the most natural career for someone like me, but I never forgot the feeling of being seen and valued.

What are some of the most interesting or exciting projects you are working on now? How do you think that might help people?

There are so many projects I’m excited about, but one that has been particularly inspiring is a project on Gen Z futures. I have been interviewing Gen Z student activists about their experiences during the pandemic, how it shaped or reshaped their imaginations around social change and what’s possible, and how they envision the future. I can’t say enough good things about young people, considering the awful hand we older generations have dealt them, and how they’re picking up the pieces and creating things in beautiful and visionary ways. They have so much to teach the rest of us about thinking outside the box and the power of imagination.

None of us can achieve success without some help along the way. Was there a particular person who you feel gave you the most help or encouragement to be who you are today? Can you share a story about that?

I have been so lucky to have the support of family and friends, the real ones who encourage you no matter how wild or seemingly improbable your vision. Among all the loved ones who have helped me keep going, I am most indebted to my sister. She, who has been there with me at every step of my journey, not only academic but personal, has been my most steadfast confidante, cheerleader, and rock.

Can you share the funniest or most interesting mistake that occurred to you in the course of your career? What lesson or take away did you learn from that?

There are lots of cringeworthy moments, but the one that I think about a lot is my interview for my job at USC, a dream job I wanted more than anything. The academic job interview is a true marathon of back-to-back meals and meetings with faculty, deans, graduate students, and the main event which is the 45 minute job talk followed by 30 minute Q&A.

By the time we got to the noon job talk, my voice was hoarse and I was off my game. Halfway through my talk, I started feeling a tickle in my throat. I took sips of water and tried to push through it, but I could feel my throat clenching as I attempted to speed-talk through my slides. And then I started coughing, and once I started, I couldn’t stop. I can’t even explain the feeling of helplessness and mortification when you have a room full of strangers’ eyes on you, including those making a decision about whether or not to hire you, and you are having a coughing attack in the most high-stakes event of your career thus far. One faculty member very kindly stood up and offered me a cough drop. It helped. I got through the talk. But I was certain I had bombed the interview, and it haunted me for weeks as I waited to hear back.

To this day I can’t believe I still got the job, but the cringey feeling is still visceral. It does remind me that — for all the moments I overthink, the times I feel like I have ruined an opportunity, screwed up a one-time chance — it is worth putting one foot in front of the other, taking the proverbial cough drop, and persisting to the end.

Is there a particular book that made a significant impact on you? Can you share a story or explain why it resonated with you so much?

In high school my mom gave me a book called Rock my Soul by bell hooks. It was the book I needed at a time when I was struggling to find my place in a very white social world, a book that reminded me that all the places I felt I was falling short — from beauty to wealth to social status — were constructs built to minimize me and my inner power. Though hooks wrote this book for and about Black Americans, I hope she knew how much she also helped brown girls like me.

Can you share your favorite “Life Lesson Quote”? Why does that resonate with you so much? Do you have a story about how that was relevant in your life or your work?

My daily mantra isn’t actually particularly profound on its face but it’s one I repeat to myself often and it brings me some peace: “Nothing has gone wrong.” Of course at the societal level, so much has gone wrong! Everything feels wrong! But this mantra is a reminder that all of the feelings that come up in reaction to the world — anxiety, anger, fear, sadness, even joy — are all part of the human experience and not things to escape from. It reminds me to let myself feel. It reminds me that all the mistakes I perceive I’ve made are part of my journey. I am not a robot, but rather a human doing human things and feeling human feelings.

How do you define “Leadership”? Can you explain what you mean or give an example?

My definition of leadership is deeply influenced by the Black radical tradition that centers community knowledge and power. I would define this leadership as an ongoing practice that integrates 1) an analysis of larger systems and structures with 2) the alignment of group values through relationship-building and community empowerment, to 3) actively advance missions of social, racial, and economic justice. You can look to an organization like the Essie Justice Group for a great example of what this looks like in practice.

Ok, thank you for all that. Now let’s move to the main focus of our interview. The polarization in our country has become so extreme that families have been torn apart. Erstwhile close friends have not spoken to each other because of strong partisan differences. This is likely a huge topic, but briefly, can you share your view on how this evolved to the boiling point that it’s at now?

One of the main findings in my book, The Struggle for the People’s King, is how over time, right-wing politicians distort the memory of the racial past to create an alternative social reality where white Americans are the new minorities under threat. All of a sudden everything from the rollback of voting rights to the recent book bans made so much more sense.

In the book, I traced these political uses of the memory of Dr. King and the Civil Rights Movement from 1980 to 2020 and, first of all, I was really surprised to find how far back these strategies go, that President Reagan was one of the first to take Dr. King’s words and turn them on their head to use them to roll back civil rights. But I was also surprised and concerned about how over time, these distortions of the past created this alt-reality where politicians could make Black and Brown Americans — their demographics, their so-called “culture,” their political power — seem like an existential threat to conservative white Americans. It helps you understand how something like the January 6th insurrection could happen. It felt like such an alarm going off that this wasn’t a usual story of political polarization, it was much more a polarization of reality.

I have no pretensions about bridging the divide between politicians, or between partisan media outlets. But I’d love to discuss the divide that is occurring between families, co workers, and friends. Do you feel comfortable sharing a story from your experience about how family or friends have become a bit alienated because of the partisan atmosphere?

The politicization of the pandemic truly hardened some of the burgeoning political divisions families have been experiencing, particularly in the wake of the Trump presidency. In my circles, I have seen friends become deeply alienated from their families for politicized stances on masking and vaccines. One friend, for example, had her first baby in 2020 before we knew much about the Coronavirus. Like any new mother, she was terrified that her baby would be hurt. She wanted any family members who were visiting the new baby to wear an N95 mask. Her brother in law who believes strongly in individual choice had been listening to pundits describe masking as an infringement on individual liberties. He said he was not going to mask, and if that meant not meeting his first nephew, so be it. He felt insulted that they would not ask but rather insist on masking. My friend was devastated and couldn’t understand why the love for his nephew wouldn’t surpass any personal opinions on masks. Months later, after vaccines were widespread and the baby was no longer so vulnerable, he would finally meet his nephew.

But years later, the hurt and resentment remain. Because it was never really about the masks or the vaccines, it was about the deeper questions about how we understand our relationships to one another, both within and outside our families. What do we owe one other? How much are we responsible for caring about and for one another? To what extent can we put hard principles aside and practice flexibility in how we think about right/wrong, good/bad? The truth is, sometimes, loving one another is not enough.

In your opinion, what can be done to bridge the divide that has occurred in families? Can you please share a story or example?

It strikes me that before we can bridge divides, we have to heal them. It feels like the difference between painting over the cracks in the wall of the house or getting down to rebuilding its rotting foundation. We can create quick bridges — the conversations that seemingly “clear the air” or commit to “moving forward” without really accounting for what happened. Yet the deeper issues will remain.

To rebuild the rotting foundation of the house takes an open commitment on both parts, and I will admit these conditions are hard to come by. As a society, we are not socialized to communicate with openness, reciprocity, and vulnerability. However, one of the most powerful tools in our possession is the power to listen without the expectation of achieving a particular outcome. Can we practice listening beyond the things we don’t want to hear? To identify the human emotions that lie beneath accusations and misperceptions? What does our loved one believe they will lose if they acknowledge our standpoint?

For some friends, this work is simply not worth their time and emotional energy, particularly when this work demands they sacrifice their own humanity and existence. I do not believe all relationships are worth saving. For those whose families are irretrievable, we can also build the families we deserved.

How about the workplace, what can be done to bridge the partisan divide that has fractured relationships there? Can you please share a story or example?

With the risk of sounding cynical, in most workplaces the priority of the bottom line is going to supersede sincere understanding and relationships between employees. Part of the question of repair would be, to what ends? Is the goal repair for a more productive workplace? A healthier workplace culture? In the growing contentiousness of the political landscape of the past decade, I can understand how many employers are just putting a big bandaid over the whole thing. For example, I have heard stories about employers instituting blanket rules around avoiding discussions of politics and sticking to “watercooler talk.”

What I do think is worthwhile is thinking beyond electoral politics and encouraging organizations to engage in internal reckonings. This can entail looking at and engaging with the company’s history — whether of hiring, retention, and promotion, worker protections, workplace culture, or even of the organization’s relationship with the broader community, engaging in listening sessions to understand how these have been experienced by workers and community members — and using this reckoning as an opportunity to rethink organizational practices, culture, and goals. Sometimes the internal work that has immediate benefits for the lives of workers and their families is more impactful than the lofty — and potentially unattainable — goals of bridging partisan divides.

I think one of the causes of our divide comes from the fact that many of us see a political affiliation as the primary way to self identify. But of course, there are many other ways to self-identify. What do you think can be done to address this?

I say this all the time, but the two-party system does not serve us. The way powerful interests have convinced us to invest so much of our identity and political energy in hardening party lines and living by them is devastating. When you look at actual social issues, much of the public is in alignment, but anti-democratic political strategists are — it pains me to say — brilliant at drumming up moral panics and creating false perceptions of threat that cause communities to double down on party identification and protection.

I believe we have reached a point in our country’s economic trajectory where our current system is not serving most of us, regardless of party. We should not be struggling as much as we are to feed our families, keep roofs over our heads, to educate our children, keep them safe, and set them on pathways of flourishing. If we could all take that eagle’s eye view and see just how much our fates are linked, our struggles are in alignment, imagine how we could come together and hold powerful interests accountable. This is very much what Martin Luther King, Jr. was working towards at the end of his life with the Poor People’s Campaign.

Much ink has been spilled about how social media companies and partisan media companies continue to make money off creating a split in our society. Sadly the cat is out of the bag and at least in the near term there is no turning back. Social media and partisan media have a vested interest in maintaining the divide, but as individuals none of us benefit by continuing this conflict. What can we do moving forward to not let social media divide us?

Media/social media literacy is so essential. Knowing this very fact — that we’re being fed negativity and controversy to fuel our outrage and keep our attention on the page — can help us take the pause to separate our feed from the real world. One of the more promising outcomes I’ve been seeing is my students placing real limits on the time they spend on social media, recognizing its harms mentally, socially, and politically.

What can we do moving forward to not let partisan media pundits divide us?

For starters we can step away from 24 hour news cycles. They rely on our eyeballs and clicks, but if we divest, they will lose their power. Instead, we can invest in local news that bolsters our understanding of the issues facing the communities where we live. We can step into the world, interface with real people, and become involved in our communities to create real change.

Ok wonderful. Here is the main question of our interview. Can you please share your “5 Steps That Each Of Us Can Take To Proactively Help Unite Our Country”.

1. Listen: Unity does not mean sameness, but we cannot know unity if we do not know the other. Knowing each other requires developing our practice of listening. Listening does not have to mean acquiescence or agreement. Rather, listening builds knowing and seeing, of one another, as humans. When we know and see, we can identify the common threads and where we might dismantle or build.

2. Educate: We must commit ourselves to a lifelong practice of critical and spiritual education. A critical education reminds us that our lives are shaped by longer histories and larger social forces and that we have the agency to change them. A spiritual education reminds us of our interconnection to one another, the natural world, and beyond. Together this education roots us in a shared vision of humanity so we can forge more beautiful worlds together.

3. Reckon and Refuse: We have to reckon with the painful wounds of the past, whether in our relationships, the communities where we live, workplaces, or the nation. We have to refuse the convenient pasts handed down by those in power with rose-colored glasses that distort our reality. By facing the past with openness and honesty, practicing a politics of refusal that centers ‘we the people’ rather than the 0.1% who seek to divide us, we can begin the hard work of repair and reconciliation to move into the future together.

4. Advocate: Advocacy can take many forms, and advocating for policies for the social good and against anti-democratic politics is but one form of advocacy that helps improve life for all. We can also advocate to care for the most precarious in our communities, whether at neighborhood committee, church, synagogue, and mosque, school board, or city council meetings. The work of advocacy brings us together and roots us in common cause.

5. Create: As humans, we are social beings born with wells of imagination and creativity. We are meant to join and create together, a fundamental building block of social life that bonds us in powerful ways. Let us create spaces for communal discovery, collaboration, daydreaming and brainstorming. Let us think beyond the world we’ve been given and begin to create new worlds together.

Simply put, is there anything else we can do to ‘just be nicer to each other’?

I want to make a quick distinction between niceness and kindness, because at times niceness can be a tool for silencing, shutting down, and even punishing necessary conflict. Niceness unfortunately doesn’t help us do the deeper, messier work of facing painful truths — which are uncomfortable and not so nice! — and working together to heal them.

Kindness on the other hand can be valuable for remaining rooted in our shared humanity. I try to practice in my collective work the same thing I teach my small children which is that kindness begins with the way we treat ourselves. Can we allow ourselves to be an imperfect human being, to give ourselves grace and forgiveness, to speak to ourselves the way we would speak to the person we love most in our lives? This internal practice can be transformative in how we treat others, especially those we don’t agree with.

We are going through a rough period now. Are you optimistic that this issue can eventually be resolved? Can you explain?

As a social movements scholar, I always remind my students that social progress is rarely linear. We have this collective idea that things should always be improving, and it can feel devastating when you fight so hard only to see things regress. But the history of social progress in the United States is the story of the Black freedom struggle, and despite halts and stops and at times going backwards before going forwards, this is a story of persistence and a commitment to a longer vision.

The goal, as I see it, is not to resolve a problem that may very well be intractable. The goal is to demand more of ourselves and our society and to engage in a collective commitment to keep doing the work together. It’s the power of the people that I am most optimistic about.

If you could tell young people one thing about why they should consider making a positive impact on our society, like you, what would you tell them?

From my experience, young people are already creating such positive impacts, if anything I draw my inspiration from them. For those who may be hesitant or disillusioned by a world that can make you feel small and powerless, I hope you will remember that we humans are, at our core, social beings. We are not meant to think and work and strive alone. We are meant to be in community and caring for, collaborating and building with one another.

Is there a person in the world, or in the US, with whom you would like to have a private breakfast or lunch, and why? He or she might just see this, especially if we tag them. 🙂

Given how much I have been inspired and influenced by the legacies of the Black freedom struggle, I would love nothing more than to sit with a true revolutionary and visionary, Angela Davis.

How can our readers follow you online?

You can find me on Instagram @ProfHajarYazdiha, TikTok @Prof Hajar Yazdiha, Twitter @HajYazdiha, and on my website www.hajaryazdiha.com.

This was very meaningful, and thank you so much for the time you spent on this interview. We wish you only continued success on your great work!

Putting The United Back Into The United States: Author Hajar Yazdiha On The 5 Things That Each Of… was originally published in Authority Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.