An Interview With Ian Benke

The fourth thing is to write with passion. Even if you’re writing non-fiction, unless it’s deliberately required to be dry and quantitative, put a piece of your soul into it. I include dreams and events that I have experienced in my books, because they are part of me –the latter especially can make things feel deep and real. A reader desires you to compel them, to engage them through the familiar and the novel; your passion shows through and inspires others, makes them care for what you write. That passion and emotion is critical — you won’t write as well if it’s a chore (and it can be a chore!).

Science Fiction and Fantasy are hugely popular genres. What does it take for a writer today, to write compelling and successful Science Fiction and Fantasy stories? Authority Magazine started a new series called “How To Write Compelling Science Fiction and Fantasy Stories”. In this series we are talking to anyone who is a Science Fiction or Fantasy author, or an authority or expert on how to write compelling Science Fiction and Fantasy .

As a part of this series, I had the pleasure of interviewing Christopher Bramley.

Chris is the author of the World of Kuln series, as well as other diverse stories, and writes articles and books in non-fiction and business. He is also a TEDx speaker, and a coach, speaker, and consultant for executives and organizations in complexity, agility, and human learning. He has too many hobbies, including a very active lifestyle, and is a strong mental and physical health advocate. He reads almost constantly. For him, life is about learning and doing. Chris is atypically autistic and has differences in sensory and emotional intensity and input, as well as annoyingly persistent imposter syndrome.

Thank you so much for joining us in this interview series! Before we dive into the main focus of our interview, our readers would love to “get to know you” a bit better. Can you share a story about what first drew you to writing over other forms of storytelling?

You’re welcome, Ian — delighted to be here.

Growing up I was always fascinated by any form of story, but reading best fitted my patterns. I went through Lord of the Rings in a week when I was eight; at twelve I had a reading age of twenty-one. At about thirteen I realized I had stories inside me that were different to what the people around me expressed, and I couldn’t work out how to express them or tell people — I had an extremely overactive imagination (now, of course, I know why). One day I got hold of an old word processor (an Apricot, with a dot matrix printer!) and started composing a chapter called “In the Beginning” — which (refined) you will find in the latest book, coming full circle. For my GCSE English Literature exam, I submitted a proto-chapter, and my teacher awarded me exceptionally high marks; for someone who didn’t engage well at school due to being different, that meant a lot. That chapter was used as Chapter One in The Serpent Calls as a tribute to my teacher, Geoff Daniel (albeit with slightly less Cyclopes and random magic!). With his encouragement, and my burgeoning awareness of Terry Pratchett, Dragonlance, and Eddings’ work, I realized that more than anything I wanted to discover and then tell the internal stories I could sense hints of.

I think my fate was sealed when I started reading those full fantasy books and marveling at how surreal it was that an entire world could exist within the pages — it almost didn’t seem possible! What was in books became part of who I was, not just something I experienced, especially for someone who felt detached from the world everyone else was a part of. They were so much more visceral, deep, immersive, permanent worlds to me than even tv/film, which only lasted while I was watching; what was in books stayed with me. Math’s doesn’t work well for me (I’m suspected of having dyscalculia), but even if I don’t look at the language elements of writing it just… it flows, I grok it, I feel it, I love the texture and taste of it (I also have synesthesia, and books fit it better than any other mediums except perhaps music).

You are a successful author. Which three character traits do you think were most instrumental to your success? Can you please share a story or example for each?

I think it’s hard to identify which traits were consistently most instrumental, but one of them has to be my sheer passion for writing, creating, thinking about, and sharing worlds and alternate scenarios, supported by discovering and learning (and doing!) everything I can. Passion over everything else can carry you through failure, rejection, anxiety, imposter syndrome. It makes what you do important and have purpose; not simply being interested, but inspired, is incredibly powerful, and inspiration beats mere incentive every time. I have countless examples of where incentive did not provoke me, but passion did — at school, having to write five hundred words felt like a lifelong challenge, whereas I remember coming home after work once and needing to write seven thousand words before dinner. It’s why I do so many activities, have trained in so many things. I have a passion for understanding and finding new patterns, experiencing what I can, and a passion for telling stories, especially using that experience. I’m very passionate, and if I do something, I generally do it right.

Another important trait is really two — the dual-faced coin of agility and resilience, which I’ve had to improve. Not being too precious about your work or mistakes, and having the ability to change, repurpose, and respond with appropriate speed is what defines agility. Resilience, the other face of the coin, is the ability to detect signals which say where failure may come, to quickly recover if failure happens, and to exploit a new paradigm if it exists. Agility and resilience are linked, innate human traits which we are very good at training ourselves out of. Where I fall down is if I get an autistic overload — my cognitive load is always high, so although I have capacity for uncertainty and excel at dealing with it, I don’t have much leeway before I shut down a bit. You can manage this with patience, experience, and understanding. There is no failure — only feedback! Real failure comes from ignoring that feedback; humans learn from failure far more effectively than we do from success, because we often assume success has a coherence that may not have existed. But it’s hard — we’ve been taught that failure is bad and that we must succeed. Redefining “success” is key to being both agile and resilient; you may feel your writing is crap, you may feel you’re not getting anywhere, you may be exhausted, you may feel constantly rejected, but the truth is even finishing draft one is a success. Fulfilling your vision is a success, even if no one buys the book. You have to absorb the lessons from all of this, keep going, and try new things, experiment, probe. As someone autistic, rejection is particularly hard for me — every day I struggle with imposter syndrome and anxiety in some form, and unfairness and confrontation is almost physically painful. If you keep going despite this, it’s worthy of even more respect; struggle against self is hard enough without neurology adding to the fray! But it’s also about being kind to yourself and not just pushing until you break down.

And that nicely leads to my last pick here: observation and dedication to detail, in my case as a result of neurodiverse aspects. Recognizing your unique strengths and allowing for their inbuilt kryptonite is crucial to the neurodiverse; the depth of detail and hyperfocus that can result can be astounding, but it can make it much harder to deal with social networking, interviews, rejection, and confrontation. There came a point when I was looking at what defined different cultures in Anaria, a continent in my main series, and I was researching the composition of the inks they would each use dependent upon the paper or source of parchment they used, and I eventually said, “Chris… step away from the computer. Go outside.” It can be a bit much — the exploration of 18.5 billion years of universal evolution just so I could justify Gods took months and sits in an excel spreadsheet, the same for calculations about how dragons could actually work — but it leads to a richness of world which doesn’t need to be in the story to exist. Just remember not to burn out to build it!

These traits aren’t segregated. They’re holistic and interlinked.

Can you tell us a bit about the interesting or exciting projects you are working on or wish to create? What are your goals for these projects?

I am currently focusing on the imminent re-launch of The Serpent Calls this Christmas (Second Edition, new cover) to prepare for a larger full launch of its sequel, Tides of Chaos, next Easter. I was considering a full re-edit of The Serpent Calls — like all first books, it has flaws — but for now I’m correcting minor errors. All the books are getting a brush-up to have a similar cover style going forward, and I am tentatively poking myself towards writing more of the short companion books and stories to expand the World of Kuln. The Serpent Calls was also supposed to have had the audiobook version released this Christmas, alongside a great video advertisement which hasn’t yet finished production (the pandemic delayed a number of projects), but a few timing setbacks mean it may have to wait until Easter as well.

I then have book three in the trilogy to get my teeth into, with the plans for book four and then trilogy five to seven after that. Outside Kuln’s universe, I have been planning to write an apocalyptic sci-fi novel for a while, as well as having a rough plan written out for a thriller/murder-mystery set within the Elite Dangerous universe. I’m planning/writing several non-fiction books within industry (in the style of the old Jackson/Livingston “Choose your own adventure” series) for things like coaching, anthrocomplexity, executive decision-making, framework use, and so on — quite fun and lighthearted stuff despite the subjects!

I also need to write another book on human learning/complexity/narratives to expand upon the very basic Involve Me (plus elements from the TEDx I gave on collaboration), but that’s going to be extremely in-depth, and I haven’t even begun planning it yet. Not quite as gripping as dragons, probably! I keep trying not to get excited by anything else and focus on the work in progress… but I am interested in so many things that it can be hard.

Wonderful. Let’s now shift to the main focus of our interview. Let’s begin with a basic definition so that all of us are on the same page. How do you define sci-fi or fantasy? How is it different from speculative fiction?

This is an interesting one to explore — I don’t really have a definitive answer. In broadest terms, speculative fiction is a super-genre which could be seen as an “expanded universe” for more tightly-bounded traditional types of sci-fi or fantasy, where we rely on current rules (science, society, et al), or history (events and chronologies) to constrain both story and belief. Perhaps another way of considering it is that we don’t have to (or can’t!) create underlying structural elements if we don’t want to stray into the realms of speculation. But outside that, I think there’s a fuzzy liminality — where do we draw the line? Is a story about cold fusion speculative fiction? Is a story about fusion no longer speculative fiction? Do we recategorize it as knowledge shifts? Recent advances in fusion experiments mean that working tokamaks are a reality now, so is everything written involving that now in a different genre? Perhaps it’s one divider between soft sci-fi and hard sci-fi.

For me, fantasy and soft sci-fi most often feels speculative — the creation of large parts of or even entire worlds, many with totally different rules (physical, biological, cultural and so on), which may be integrated with, or fully separate from, our own reality or time. I remember having an interesting chat with Scott Lynch at WFC2013 about sci-fi being a subset of fantasy, and when you look at the interesting crossovers that Iain M. Banks did with Inversions, or Tad Williams did with the immense and intricate Otherland series, it’s easy to see how lines get blurred. And then we return to that division oft-argued between soft and hard sci-fi — I guess for me, soft tends towards fantastical or created speculative elements, where hard tends to be as realistic as possible in line with what we understand, but where we’re still creating a story which is obviously not our own context (Neal Stevenson’s Seven Eves started feeling sort of hard but moved very quickly into soft for me). I must be honest, I try not to get too hung up on specifics — I think it provides too much argument for fans. I’d rather people argue about what happens in the books instead of where the books belong.

In Speculative Fiction, a mirror tends to be held up to our own world (iirc Neil Gaiman spoke of this as being a requisite a while back), and explorations can be wild or familiar. For my own books, I’ve had multiple different genres put forward by different readers (horror, epic/high fantasy, grim, classic, thriller), and a lot of the more magical elements are low-key based on current scientific theories, so I have no idea where that really leaves them. I don’t really fit neatly into a “fantasy” box. I’ve been considering simply going with “Speculative Fiction” instead of fantasy or sci-fi… maybe I should do that.

It seems that despite countless changes in media and communication technologies, novels and written fiction always survive, and as the rate of change increases with technology, written sci-fi becomes more popular. Why do you think that is?

The richness of exploration of concepts and pathways can be fully — and I think less confusingly — explored in reading sci-fi, whereas in visual media the constraints of time and lack of additional context mean that anything outside visual representation may be harder to impart. This isn’t as true in a series, but there’s a reason that multiple films are often needed to cover one book properly (the recent Dune did a grand job of it for the first half at least), or multiple series are usually needed to cover many books. To fit concepts into a few hours there are inevitable shortcuts which books don’t really have to make, and this then changes pacing considerably, with visual media outstripping books exponentially (as in Game of Thrones). The impact of film and tv can’t be denied — SEEING something can take your breath away in a way which written words may not achieve — and yet the richness of meaning may be less, or even non-existent. In a way, I think books have to work harder to make something feel immersive, where “seeing is believing” means we may accept things more readily visually and aurally (especially when it’s overwhelming), but we also recognize that AV media is a more temporary escapism. Books can make me feel like I am truly in another world, not by sensory overwhelming, but by convincing. Now, this answer may significantly change as newer tech develops — ask me again when VR is more mainstream! That is where we may see more crossover. But even then, books give context outside the events which you wouldn’t get readily otherwise (without limited voiceovers and so forth). Books contain many voices, and can jump between them in a way other mediums can’t without losing a vital thread.

But to come back to written sci-fi: at a more abstract level — although tech intersects well with books, especially when travelling, and we consistently explore new ways to absorb books — people still love paper novels, and there’s a lot to that. Studies show we read differently from paper than from screen — we absorb information differently, and there’s also a tactile element alongside an unchanging structure of text which is lost with markers and responsive layouts. I think there is an emotional response from having physical books which is hard to replicate with devices, and a requirement to pay attention to the information in a different way. Writing on something — to create what Jack Cohen called “Extelligence” — was the first way of preserving information long term against human error in recall, and I think we still have an attachment to words on paper. Turning a page can feel almost holy in a way swiping can’t. It’s even built into our languages. And as I mentioned previously, screen tends to be in-the-moment; what’s in a book stays with you and lets you think about it over time, maybe even re-read with new layers of understanding. But will that stay true if future generations only have devices? Hard to say. I only know that for myself, reading a real book is infinitely preferable to any kind of technological proxy. I’m not a fan of listening to audiobooks either, so a future where a warm-voiced AI soothingly reads me my story is less appealing than an AI who says “you still read those out-of-date paper things?” and I say, “yup.”

Lastly, books simply cost more in time for a reader. You have to want to read a book — it’s not a background task. It takes dedication and effort other more passive mediums don’t always have. I can tell if I love a picture in seconds, at least under a minute. I can tell if I like a song in a minute, and it lasts for maybe five. A film passively takes a few hours of my time. But the detail and scenarios in a book can take me a fair while to read if I don’t get an uninterrupted session in, and it’s not that passive — I have to generate everything internally from a linear data stream, which is a lot less natural than simply looking or listening. This means it’s more personal, unique to me, and likely richer as a result. We watch screens; we invest in books. One is consumed, and one is absorbed. Each has their place; maybe we’re growing tired of simple consumption and are searching for deeper meaning.

In your opinion, what are the benefits to reading sci-fi, and how do they compare to watching sci-fi on film and television?

We’re at a fascinating point in human history, and something a lot of my work outside fiction touches upon. There are a few elements I think are at play here: for the first time in human history, our tools are evolving faster than we can keep up with; also, generational mindset is different — for millennials and post-millennials, tech is not seen as a tool, but an integral and almost invisible part of life in many countries. When you combine that with the speed of communication, and the multiple pathways of possibility, you can see why there is a fascination with what might come next. I think there is also a newly-tangible element to sci-fi — with the increasing rate of change you can almost feel the next breakthrough, it’s as if it’s just at fingertip-touch. In some ways, the increasing tech itself excites sci-fi, as it’s almost physical proof of fiction become reality. With greater access to more information than ever before, readers may well want the detail-rich scenarios modern sci-fi and fantasy offers because their general understanding of tech is at a level many previous generations would never comprehend. There are now great examples of both art imitating or evolving life in sci-fi, and life inspired by art in a reciprocal cycle (Star Trek has a fair few).

Don’t forget, too, that newer generations have in many ways less than before — it’s harder to own houses, make money, fit into a two-hundred-year-old work paradigm which is at odds with modern ideologies and sustainability, and much more, and there’s a far greater awareness of the breadth and fragility of our one world, our impact on it, and individual opportunities in general, so it makes a lot of sense that they’d yearn more than ever for stories of how that might be different, evolve, or improve. Sci-fi gives us glimpses and hope for the future, and it’s become mainstream enough that it’s accessible to us all.

I think film and tv are wonderful temporary escapism, and can affect us deeply, but I don’t think they can do so — and teach — as books do. A film also stays robust — that is, the shots are unchanging and set — but a book is adaptively resilient in that it can actually conceptually change over time as you change and revisit it, because the book is an immersive enabler for scenes you create yourself, not a delivery mechanism for scenes set by someone else. Don’t get me wrong — I would love to see my books brought to life in stunning visuals on Netflix, but a lot of the richness and layering of the world would likely be left out.

What authors and artists, dead or alive, inspired you to write?

So, so many. Terry Pratchett — whom I never quite managed to meet — was one of the most influential, but a lot of the greatest writers out there (some of whom I’ve had the honor of meeting) have had a profound effect upon me — Anne McCaffrey, Frank Herbert, J.R.R.Tolkien, Neil Gaiman, David Eddings, Iain. M. Banks, William Gibson, Robert Jordan, Brent Weeks, Harry Harrison, Raymond E. Feist, Tad Williams, Robert E. Howard, H.P. Lovecraft, Terry Brooks, Peter F. Hamilton, Jackson/Livingstone, Jack Cohen — to name but a few. There are so many more! Each of them not only showed me worlds they inhabit or glimpse, but inspired me to share my own, and for their work and craft I am profoundly grateful. Amongst books that inspired me most when I was young were the Belgariad/Mallorean, Dune, LOTR, Discworld, Magician, Dragonlance Chronicles, and The Stainless Steel Rat(s) which offer superb social commentary. There are many more from the golden age of fantasy and sci-fi through on.

If you could ask your favorite Science Fiction and Fantasy author a question, what would it be?

Ha. Probably “Will you read my book?” in a misguided attempt to give something back creatively, but I’d likely be too anxious to actually ask it and worried they wouldn’t like it or that I was impinging on their time. I’d probably focus more on how they write and what works for them; it would be very interesting.

We’d like to learn more about your writing. How would you describe yourself as an author? Can you please share a specific passage that you think exemplifies your style?

The way I write is quite different to many authors I know, although we’re all different. I don’t often suffer writer’s block, more writer’s demotivation, but I get sizzling images in my head and write random scenes (either new or from the plan) in a frenzy, quite randomly, and sometimes the urge to get words down is like a torrent which bursts forth. Other times I construct (usually between scenes). I sit down and try to arrange scenes chronologically in line with my poor, oft-abused pre-book synopsis, and then I try to understand the linkages and patterns between them before smoothing it down for flow, almost like a piece of clay. After that, I dial back the granularity and see if it makes sense from afar. What I can’t do is write exactly to a plan beginning to end, in sequence.

It’s very hard to describe myself outside this! I am a detailed and visual writer, but I value real characters and the flow of the story very highly. I’m told that people reading my work can imagine seeing it as if they’re there, or that it would translate very well to the screen, and I tend to “see” it happening as I write, as if I’ve been granted a window into another universe. Other than this, I have a blend of styles — I don’t believe a book should be just one thing, so there’s humor, sadness, horror, epic fantasy and more in each book.

I thought I would share two passages to show differing aspects of my styles, one more focused on action and the world, and one focused on the intimacy of the characters:

Leona approached a mossy mound of rocks that rose amongst the silent trunks, the silence prickling her. Her eyes pierced the gloom with ease. She saw nothing out of place. There was no movement around her, but she felt hostile eyes watching her.

This was where the creature waited, knowing it was hunted. Her ears twitched; a faint rasp of breath reached her, deep and ragged. She could not tell where it came from.

The stench of the creature lay thick, underlaid by the coppery smell of blood. The scent was everywhere.

Her hand crept to her worn club, willingly given from a solid root, but she knew against this foe it would be of limited use. She would need to draw on other powers to prevail here. Slowly she crept forward along the side of the mound.

A roar was her only warning, talons scraping on rock as her foe launched itself from the top of the mound at her back. She flowed underneath the huge creature as it sprang, spinning and lashing out with her weapon. As it struck with her full weight behind it she yelled. The air shimmered and distorted unnaturally around the club’s impact.

Although many times her weight, the monster was smashed brutally aside by her augmented strike as if it was a child, and she whirled upright, ready. She had dealt a blow that would have killed a bear, but that would only slow it for a few seconds.

The creature had tumbled fifteen feet, slamming into the mossy ground. It twitched, then rolled with frightening speed to its feet to face her. A heavily muscled torso heaved with great wet breaths. The clawed hand rose to its damaged side.

The stink of it filled her nose, a raw and feral musk. Its eyes were terrible lamps, oversized fangs dripped with saliva beneath as it glared at her through bright yellow irises. Taloned appendages that were neither hands nor true paws clenched in anger. Young as it was, it was powerful. It did not know why it hated her; only that it did.

It roared in challenge, a terrible sound.

Fury and a terrible aversion swept through her. Dropping her club, she cast her robes wide, ready for battle. She needed more primal powers for this enemy. Her vision filled with red as hate that matched and overmatched the terror in front of her erupted within, and her answering snarl gave the beast pause.

Leona summoned her powers and leapt.

‘Boy!’ a deep woman’s voice called, and he turned to see another veteran running towards him with only a sword. He regained some of his senses. Anyone alone would die. They needed to regroup to get back to their fellows alive.

‘Ware!’ shouted Karland, seeing another horse galloping in. Without even looking she tried to dodge, but went the wrong way, crossing its path. The shoulder of the horse clipped her from behind and hurled her into him. Karland went down with her on top of him.

The breath was blasted from his body, and he hit the ground hard, stunned. It took him a moment to collect himself enough to start to push her off him. He didn’t know her other than by sight. She was much older than he was, her square-jawed face lined at the eyes and with a mole on her left cheekbone which enhanced her looks rather than marred them. He gazed into her face. This close, he could see the dirt from the road in the pores of her skin, hear the agonised whistle of air past her teeth when she inhaled.

The soldier was more dazed than he was, and whimpering in pain, favouring one arm. It looked as if the impact had dislocated her shoulder. They lay there for a moment, his wits clearing.

Even as she began to try and rise off him, hoof beats sounded again nearby, thudding past. She jammed into him hard, knocking more breath from him, and then stiffened, her mouth in an O, looking into his face as if she had only just seen him as clearly as he saw her, perhaps wished to kiss him. Her eyes were blue-green, with the most lovely patterning in the iris, and they flicked around his face for a second, searching for something. She shuddered, exhaling into his face, and slumped on him. The metallic tang of blood carried on the breath, and a gasping from her throat went on and on as she tried to breath in again with lungs that no longer worked. Karland sobbed at the intimacy of the death. He held her as she shuddered, smoothing her hair to try and let her know someone was there.

It must have been only seconds later that she lay stiller than still, and he knew she was gone. He pushed her off him, tears blurring his sight, an awful gash in her upper back where a passing knight had jammed the splintered end of a lance with punishing consequences. The lance lay thrown aside, the end dark with blood.

Trying to collect his bearings, Karland looked around through his tears. He was cut off from relative safety by the Novinian infantry and dismounted knights were attacking his countrymen with zeal, wielding longswords, maces and axes. More than thirty horses stamped riderless behind him, nervous in the din of combat.

Based on your own experience and success, what are the “Five Things You Need To Write Compelling Science Fiction and Fantasy Stories?” If you can, please share a story or example for each.

The first on my list is to write as much around the story as for it. I have a map of Kuln in Photoshop which is one pixel for every mile of the planet, and has layers with tectonic plates, climate, trade winds, major currents… you see a fraction of this reading the book, but it’s there. The depth and breadth in your world are the warp and weft of a canvas; you paint the story over the top, and the texture shows through and enhances the whole. Creating a world can’t work like a game, where you only generate the polygons you see; if you want it to live, to breath, it needs to have richness and path dependencies that exist whether they’re directly in the story or not. Especially for Speculative Fiction, you have so much more work to do than just describing events; you have the underlying dark constraints (cultures, traditions, languages, castes, divides, superstitions, flora, fauna, landscape, and on) which define the setting, and you have to describe everything and expand on it because it doesn’t exist and you need to reader to have enough to see what you see. So you have to build assemblages, which are a coming together of stories within your story, and affordances, which are what the characters are offered by the environment they exist within, to consider as well. I mentioned earlier about my creating the inks and written mediums for each culture! You can see why many authors fall into the trap of getting lost in too much detail (that’s why everyone needs editors and draft readers), so you need to find the balance where the world breathes and lives, but you don’t bore people by describing the nine folds of cloth on the arm of one character when they walk into a room, or you distract from a fast-paced scene. Going back to the analogy of a canvas, how much you leave nebulous and how much is important to describe is variable and a constant call.

The second is that, whilst this beautiful world has been brought into existence — in potentially exquisite detail! — your book shouldn’t be primarily a showcase for a setting. True narrative and story is driven by the characters, and not just what they say or do, but how they feel and think, act and react. It doesn’t matter if a story is set in a world with dragons, oscillating-field self-aware drones, or people catching the bus — if your characters are realistic, inspire empathy, your story will be engrossing. The follow-on from this is that there are a number of things characters need to become REAL people, and it’s very easy to become so focused on the world itself that the characters exist only to move you through it. For me, you’re more likely to believe you could be in a world if the characters act like “real” people — are different, complex, people you identify with, who have histories, challenges, surprise you, make you laugh, who you are afraid for… often most powerfully, can see yourself as or with. It’s that connection — a twinned empathy and compassion — which draws us to protagonists, and that fascination — with darker sides of ourselves, or something totally alien perhaps — which draws us to antagonists. This, I think, is where we love antiheroes so much — we get to experience both, with a foot in the light and the dark. One of my characters, Grukust, initially seems like a typical, simplistic barbarian plot-device creature. He doesn’t speak very well, but in fact he’s an onion of sly wit and intelligence, with different cultural drivers, and he speaks his own language very well indeed — you begin to realize he’s a real person, even if he’s not human, and I still haven’t found all his layers.

Thirdly — do your research! If you are writing anything with depth, you need to understand (at least in part) what you write about. Nothing yanks me out of immersion faster than something which is ridiculous or untrue, especially used as a plot device. Not to say you won’t make mistakes; all authors do (and new editions try to pretend they didn’t happen, sometimes!). But a chance miscalculation on how far a horse might move over certain terrains is one thing; simply not knowing what you write about is another. I am extremely uncomfortable when an author crosses the line from reasonable speculation into discernibly being incorrect, especially as deus ex machina. This is perhaps more obvious to me due to autism; I notice extreme detail. But it’s one reason I do so many things; I learned to forge my own wedding rings, I am an archer, diver, climber, martial artist, musician, and more; I know exhaustion and loss and dread through (sadly) intimate experience. Every new thing I learn makes my writing richer. I may not do any of these things as a world-class participant, but I know enough to write about the experiences, and that means what I write is real — even when it’s not. It’s a funny thing to say, but… don’t just make stuff up while you are making stuff up! If you’re pushing the boundaries by speculating, it’s important to make that clear, otherwise you end up with perfect messianic characters and events happening that simply are impossible in any world (and even worse, may contravene your own narrative laws!). You can get away with a certain amount through cool factor, but personally I temper it with reality so people can identify; “cool” doesn’t automatically mean you should include it.

The fourth thing is to write with passion. Even if you’re writing non-fiction, unless it’s deliberately required to be dry and quantitative, put a piece of your soul into it. I include dreams and events that I have experienced in my books, because they are part of me –the latter especially can make things feel deep and real. A reader desires you to compel them, to engage them through the familiar and the novel; your passion shows through and inspires others, makes them care for what you write. That passion and emotion is critical — you won’t write as well if it’s a chore (and it can be a chore!). There’s nothing wrong with sometimes just “constructing words” — all books have this somewhere — but writing is like music: you can be perfectly technically competent, but that’s not enough for people to feel the emotions. As important as the passion, scenes, and world is the cadence: it has to flow. One of the most amazing, alarming things when I was writing The Serpent Calls was when I wrote one day almost in a trance — a few thousand words at once. I finished in despair, because I had written something I didn’t want to happen, and I went back to remove it — and realised that if I did so I would change the story. It’s humbling to realise that the story is alive and uses you as a conduit sometimes, that you may not be in charge — that you have a muse, I suppose; I’ve experienced this composing music, too. That part haunts me, because I never planned on it, didn’t want it, but it had to stay. It makes me tearful every time I read it. I want to reiterate Neil Gaiman’s quiet, powerful words from a conference I was at: he said, “write what the fuck you want” — put down what you believe in, whatever anyone says. Write your truth with all you have. Let your passion pour out of the words into your reader; ignite their passion in turn. Who knows how many people you may inspire — even other writers. If you feel your work, others will too.

Finally — be kind to yourself. Give yourself understanding and space for the story to work. Take enough breaks, give yourself distance from the work and let it sink in, see how it tastes, feels, flows. I have a saying across much of my work: it’s hard to navigate when you’re too close to the sun. Sometimes you need to step back to see the entirety of the thing! Your work will thank you and be better for you giving yourself and your story space and balance. It’s amazing how new ideas can emerge. This isn’t just about burning out or tunnel vision, though; it’s also about finding your own best path. Structure your writing methods how works best for you; there is no best way to write apart from getting words down in some way, preferably consistently. That’s it. How you best do it, what tools you use, what superstitions or rituals you require, how you plan… they’re unique to you. And lastly, be aware of your mental health. Writing can be much harder than people think, and it’s easy to blame yourself for lack of inspiration, writer’s block, missing deadlines, and as creatives many fiction authors suffer poor mental health and neurodivergence — it’s what gives us vision, but it’s also punishing. I mentioned burnout — the pressures, urges, demands, drives can really damage you, which does you, your readers, and your story no favours. Sometimes… make sure you stop, take a breath, gain some distance. Step back from the sun for a spell; and if you find that hard, make sure there are people outside your context to help you do it. The moment I accepted it was ok not to be ok when writing, and that sometimes I needed to take a break from it, was when my writing began to evolve.

We are very blessed that some of the biggest names in Entertainment, Business, VC funding, and Sports read this column. Is there a person in the world, or in the US, with whom you would love to have a private breakfast or lunch, and why? He or she might just see this, especially if we both tag them 🙂

Oh, now this isn’t fair! One person?! So many in so many areas, especially those who’ve influenced characters. Some characters were written specifically with people in mind — Rast, one of the main protagonists, I’ve always felt best based on Jason Momoa (with a touch of Aragorn), and Grukust is pretty much Dwayne Johnson (with hair and tusks) — chatting to either about playing those roles would be a dream. Councilor Ulric is absolutely Arnie, and I tried (and failed) not to read the audiobook parts for him in his voice (very badly), but I’d love to tell him how much I’ve admired his work and life. The same holds true for power friends Sir Ian McKellan and Patrick Stewart. I think Zendaya is exceptional in her roles so far, and I would also love to talk to Cate Blanchett about her polarised roles in LOTR/Thor and how she channeled them. I’ve always wanted to chat general fantasy geekdom with Vin Diesel, too!

I think it’s obvious I’d love to chat to Neil Gaiman properly about many things, and a lunch with Tad Williams would be most excellent to chat about how his work has influenced mine. I feel that lunch with Elon Musk would be fascinating — we’re both quite passionate about technical things, and although I don’t agree with everything he says or does, I think he’s genuinely intent on changing humanity’s story. In many ways, I’d really love to chat to Tom Hardy again — we were at school together, though not close, and I’ve enjoyed his work over the years. I’d love to share my own creative work in turn and catch up (in fact, I ended up writing Captain Dorn based on him).

I’m very interested in people so there are loads more. I always worry, however, that I’d simply be saying what others have said before, and about how to talk authentically with people dealing with that all the time. Imposter syndrome is a rather large part of my autism…

How can our readers further follow your work online?

My new website has just launched at www.christopherbramley.com (no shop yet!)

I tweet about a range of topics including books and writing at www.twitter.com/christopbramley

My instagram is https://www.instagram.com/chris_bramley/ (be prepared for random photography, climbing, books, diving, and various diverse things)

I’m active on www.linkedin.com/in/christopherbramley as well.

My Facebook https://www.facebook.com/christopherbramleyauthor is sorely in need of updating — I’m not on Facebook much these days.

Thank you for these excellent insights, and we greatly appreciate the time you spent. We wish you continued success.

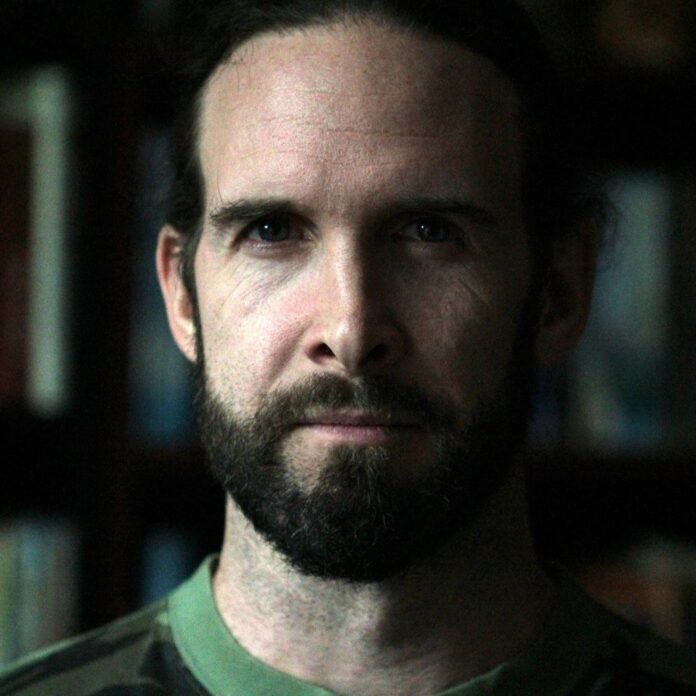

About The Interviewer: Ian Benke is a multi-talented artist with a passion for written storytelling and static visual art — anything that can be printed on a page. Inspired by Mega Man, John Steinbeck, and commercials, I.B.’s science fiction writing and art explore the growing bond between technology and culture, imagining where it will lead and the people it will shape. He is the author of Future Fables and Strange Stories, the upcoming It’s Dangerous to Go Alone trilogy, and contributes to Pulp Kings. The CEO and Co-Founder of Stray Books, and an origami enthusiast, Ian is an advocate of independent, collaborative, and Canadian art. https://ibwordsandart.ca

Author Christopher Bramley On How To Write Compelling Science Fiction and Fantasy Stories was originally published in Authority Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.